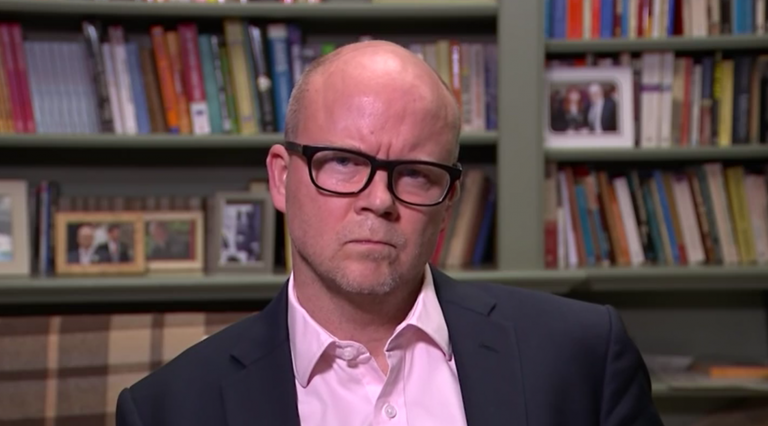

The free school founder and former columnist Toby Young has been appointed to the government’s new Office for Students (OfS). The body aims to open the universities sector up to more market competition. It is the biggest change to higher education oversight in a century. Here, Young speaks to Cherwell’s Tom Beardsworth about his time at Oxford, his views on state education, and the left wing politics of his father.

Sat outside the Turl Street Kitchen I look up to see a mediocre William Hague lookalike approaching. It’s Toby, of course, and I find him transformed from the social liability of How to Lose Friends & Alienate People to the affable and focused founder of the West London Free School. The story is hilariously well told, documenting his attempt to break into the close-knit celebrity circles of the States, from his pilgrimage there in 1995 to his escape home five years later, tail flailing between his legs. On the face of it Toby has every reason to be fed up with life. A low point perhaps was when Simon Pegg, having just come from Run, Fatboy, Run, was told to ‘fatten up’ in order to play him in the film adaptation of How to Lose Friends.

Yet Toby Young is now far from the hapless caricature he presents. The son of Michael Young, a Labour peer, his upbringing was political and firmly anti-establishment. Lord Young drafted Labour’s radical 1945 manifesto and was a leading protagonist on social reform, championing comprehensive education, a struggling system Michael Gove’s free school project threatens to dismantle. He “wasn’t very keen on meritocracy” despite famously authoring that phrase as New Labour’s public philosophy. In the past Young has called his father a “blinkered ideologically hidebound socialist” and he is largely critical of his beliefs, if affectionate towards the man himself.

The inter-generational irony personifies the turbulent history of British state education. Despite persistently failing at state schools, Toby wasn’t entered into any of the local private schools which were surely within his parents’ means. Though never bitter, he clearly abhors the worst of the state system. “Having seen how bad state schools can be I was nervous about sending my own children to the local state school.” Isn’t this just a naked appeal to self-interest? It’s perhaps a less noble motivation than those which fired his father’s ‘utopian socialism’ a generation before. Would he be turning in his grave? “I think he would have applauded groups of parents, groups of amateurs, coming together to try and take control of a public service. He believed that small was beautiful.”

And that’s the point of free schools; that in devolving power locally to extraordinary individuals you can harness their energy and innovation. The parents of West London certainly think so: in its inaugural year West London Free School attracted almost ten applicants to every place, making it the most competitive state school in the country. However, last year only 24 free school ap- plications were approved; the vast majority failed to make a viable business case. I put it to him that private capital may be the answer. After a lengthy pause for consideration, Toby endorsed the idea: “Provided the market is properly regulated, there is no reason why for-profit educations managements organisations (EMOs) shouldn’t be allowed to set up and operate free schools” with “an array of minimum standards to which all schools need to comply”.

As for the concerns that free schools will suck the best teachers and pupils from neighbouring schools, he argues “a bit of competition is no bad thing. People are a bit wary of hitting that note too hard because it seems a bit cut-throat…but I’d argue it has a positive impact [on surrounding schools].” This is the revolutionary principle that may strike the heart of the British educational establishment; that you should be able to shop for education like you do for groceries or foreign holidays. If rich parents can pay for choice, why can’t everyone else?

I was yet to fully comprehend what drives Toby; I hadn’t quite gleaned that anecdotal nugget which, once revealed, allows all the other facets of an interviewee’s character to fall into place. Then he helped me out: Toby is a Brasenose alumnus, but really he shouldn’t be. Having successfully applied, he needed to meet the unusually generous offer of three ‘B’s and an O-level ‘pass’ in a foreign language. Failing to exhibit the immodesty that would later make him famous in America, Toby told me that “my father and I concluded that getting three A-level B’s was simply beyond me.” And right they were; he received a ‘C’.

Remarkably though, “I got this letter, and it wasn’t addressed to me personally, but it was evidently sent to successful candidates.” Alas it was a mistake. A week later he received the personal letter confirming he had failed to get the requisite grades and “wishing [him] success in his university career”. Despite an embarrassed Toby imploring him not to, his father rang up the college to explain the predicament. What ensued between the PPE tutors was an extraordinary philosophical exchange about whether a clerical error was grounds for admission. Apparently it was.

The lesson: that what constitutes success is marginal; that failure can be so easily grasped from its jaws. And whilst he had plenty of the latter, he excelled in student journalism. It was, he confesses, “my only real success”. He started a new magazine, based on the insight that – with a nod to Cherwell and Isis – “if I named it after a bigger river it would be a bigger magazine. I came up with the brilliant wheeze of calling it after a different river for each issue, the first being the Danube.” It only lasted two issues, though he subsequently became the editor of Tributary, Oxford’s now defunct equivalent of Private Eye, whose previous editors included the Anglo-American journalist Andrew Sullivan and the historian Niall Ferguson.

Toby was by all accounts, an awful Union hack. “I was extremely unsuccessful; no one voted for me. I failed to get elected to Treasurer’s Committee [now Secretary’s Committee]. I got nowhere.” He had competition though; Boris Johnson and Michael Gove were both contemporaries. No doubt the London mayor’s famous bombast in the Chamber trumped Toby’s somewhat pernickety campaign. The two have been friends since their days on The Spectator. He reflected, “I spent Saturday night at Boris’s victory party, which I probably wouldn’t have done when he won the Presidency of the Union.”

Showing how far he has strayed from his Labour roots, in 2002 Toby famously made a £15,000 bet with Nigella Lawson that Boris would be Tory leader within 15 years. What about his own political ambitions though? No doubt he would relish the opportunity to rile up lefties – “I’ve always enjoyed baiting liberals.” Toby has the CV, the connections and a unique brand of ‘anti-charisma’ that could carry him into Parliament. He’s ambivalent – “Being an MP would remind me of those Oxford days shinning up the greasy pole.” Though he didn’t say as much, he considers what he does to be political.

His radical impulses are satisfied by free schools, which he wants to do more with. A book, about “class, education and British society” is also in the pipeline. Though thoroughly hostile to Lords reform, he is enticed by the opportunity it presents. “I might stand for election in the House of Lords if indeed the changes that the Coalition are thinking of introducing [85% elected second chamber] go through.” Toby Young is a colourful character. His haphazard career. his cheerful approach to failure – “failing upwards” as he puts it – and his DIY approach to solving social problems are all endearingly British. Not in the foppish style that has served Hugh Grant so well in Hollywood, but rather actually endearing to the British. He’s like a train without tracks; forceful, unpredictable and bewildering. And remarkably successful, if he won’t mind me saying.