Under normal circumstances, asking me to write about a filmmaker who’s changed my outlook on life might invite something moving. There are plenty of directors, after all, who have that effect. Scorsese’s parade of doomed hyper-masculine protagonists marches on like a premonition. Francis Ford Coppola’s best work touches perfectly on the ways unremarkable people react when everything falls apart. Or, on the lighter side, I could muse for hours on the simple joys of Wes Anderson; a man I’ve never met and never will, yet who reminds me of an old relative who effortlessly evokes long-departed times and places.

For all their merits, though, none of those three ever drunkenly told Sean Connery to ‘f**k off.’

Martin McDonagh, above all else, is an idolater. His plays, unapologetically drawing on his Irish roots, appalled the stuffed shirts of Fleet Street with their violent, absurd depictions of working-class life – but at the same time, caused a furore across the sea on the grounds that McDonagh, a Londoner by birth, was stereotyping his homeland for his own gain. He might now sit at the head of British film and theatre but if that head were to meet a similar fate to those of his protagonists, it might make for grisly viewing.

The chaos inherent to his films is perhaps best exemplified in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017), in which Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand) erects the titular fixtures in protest at the police’s inability to find her daughter’s murderer and rapist. This seemingly reasonable frustration leads to a small-town death spiral: a suicide, a defenestration and an arson attack, all stemming from the attempts of the parochial and the powerful to protect their reputations.

America as depicted in Three Billboards is angry and fractured. However, while this perspective on the country earned critical acclaim, it also provoked the ire of some quarters in the media. The film’s portrayal of race was especially criticised, with the bigoted and violent Officer Dixon (Sam Rockwell) becoming an apparently sympathetic figure despite not changing his ways. It’s true that Dixon and Mildred grow closer as the film progresses. But rather than assuming that this signifies an acceptance of Dixon, one might easily see it as a symbol of Mildred’s descent into amorality. Everyone turns against Mildred, so she turns against everyone – audience included, as it turns out. She sympathises with Dixon not for his hateful views, but for his ever-present anger at the same world Mildred sees as having failed her.

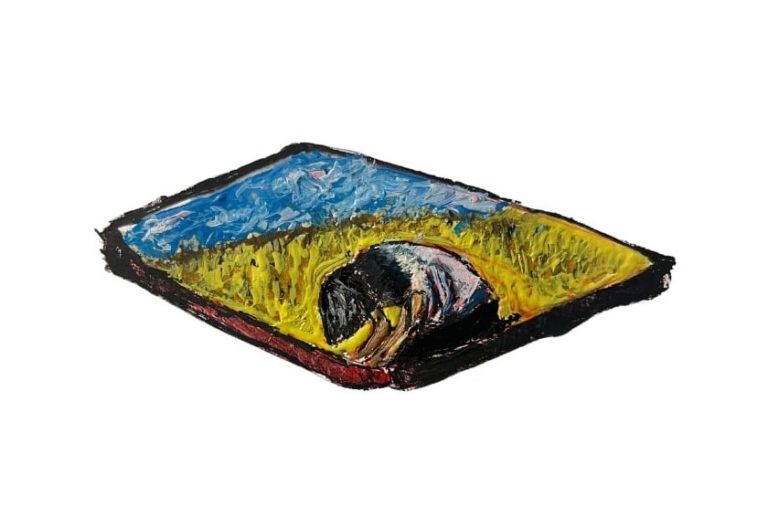

I’d suggest, therefore, that McDonagh’s handling of racial issues is more nihilistic than ignorant. Themes of cruelty and depravity also run through In Bruges (2008), in which Colin Farrell plays Ray, a hitman driven to suicidal thoughts at the guilt of having killed a child is hunted by his colleague Ken (Brendan Gleeson), who is instructed to kill him in response. The same two actors reprise in similarly bleak roles in The Banshees of Inisherin (2022). In the midst of the Irish Civil War, Gleeson’s character Colm cuts off his own fingers for no reason rather than to avoid talking to his former best friend Pádraic, played by Farrell. In response, Pádraic attempts to burn Colm alive in his own house. Scenes such as these demonstrate McDonagh’s worldview; bitter conflict is practically a given, and the only things more fragile than his protagonists’ social bonds are their egos.

In McDonagh’s work, no one is safe from corruption. The strong female lead joins forces with racist thugs, alienates her son and wishes a violent death upon her daughter on the very day it occurs. The two inseparable friends see their country torn apart by sectarian violence, and mutilate themselves for the sheer sport of it. This conception of society – one without heroes or convictions, dominated by self-destructive vendettas – is striking because, in our uncertain century, it speaks to us more than any traditional morality tale could.