Flash forward 100 years. Surprise! People still read — just not in the same way as we do now, and we can be pretty certain that books will be around for a long time yet. The future of reading, however, is shrouded in the mysteries of new inventions and technological advancements. The way people are reading is changing. Books are not only printed on paper but available on devices as eBooks and recorded as audiobooks. Almost every book is available in various forms. Reading has never been more accessible but does that mean that people are reading more?

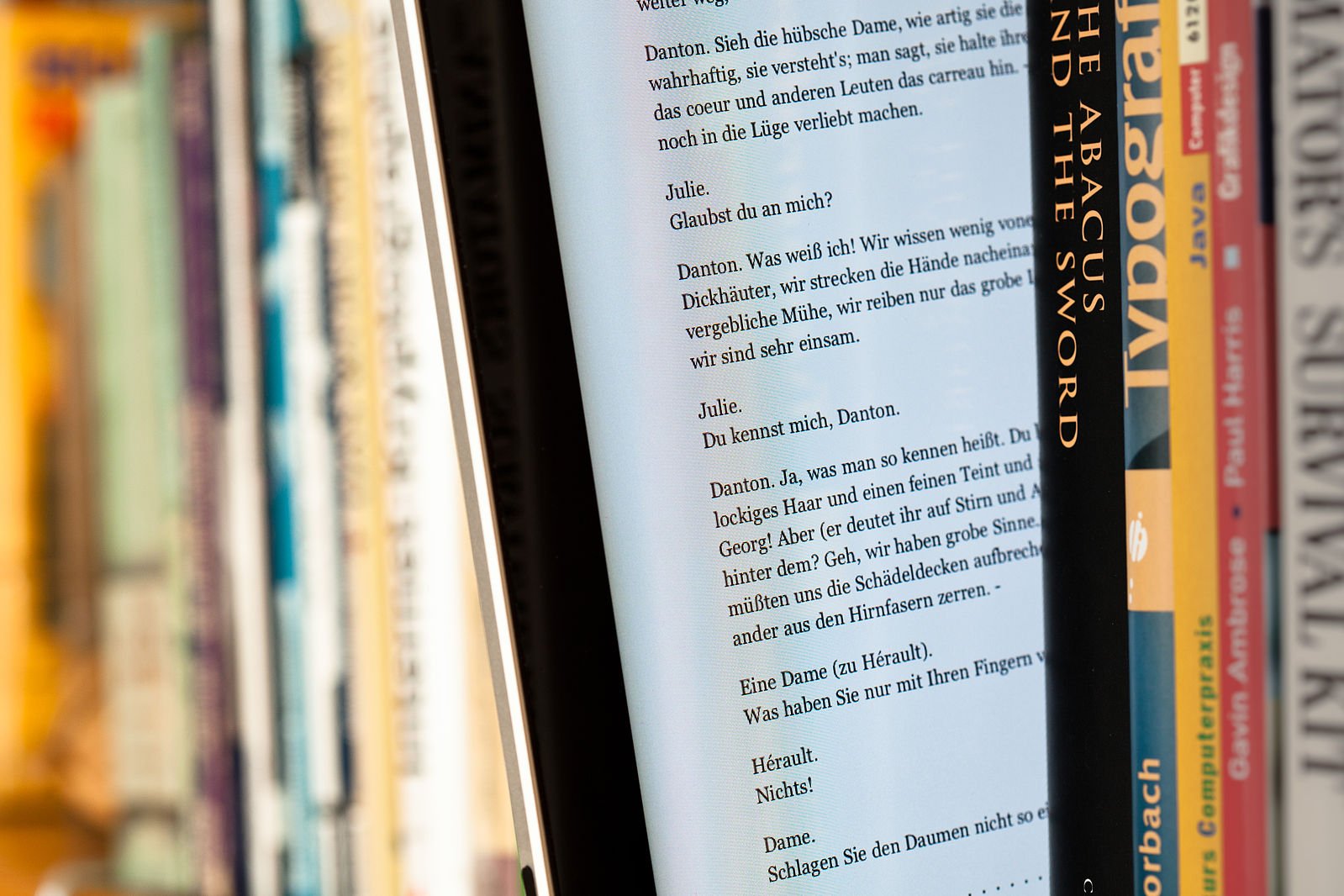

Audiobooks and eBooks continue to rise in popularity, but is reading from a screen or listening to a podcast en route to the library really as beneficial as old-fashioned reading? Not only do we read books for enjoyment and escapism, but reading also improves cognitive and language skills, increases concentration and affects our emotional intelligence. In 2019, only 54% of UK adults had read a book in the past year. Despite this, eBooks and audiobooks have expanded the world of reading. eBooks fulfil the 21st century desire for instantaneous everything, with practically any book ever published just a tap away (oh, the dangers of Amazon’s ‘just one click’!). Beyond the obvious convenience, audiobooks have also captured people with engaging voices and a return to childhood ‘storytime’.

Over the past two decades, with the emergence of eBooks and audiobooks, print has become a changing industry. While eBooks, once heralded as the future of reading, are popular, print is still king. In 2017, a survey found that 35% of respondents preferred reading from physical books, while only 5% prefer to read from digital books only. However, like many aspects of life, the pandemic caused a detrimental hit to the print market and sales plunged in the first half of 2020 by £55 million. The Guardian reported that after six straight years of a decline in eBook sales, the pandemic has resulted “with sales home and abroad up 17% to £144m in the first half.” The convenience of eBooks acted as a temporary substitute for printed books while confined within the walls of our homes, as well as a reprieve for the Amazon delivery drivers; however, for many avid readers, eBooks are not a permanent replacement. Merely Halls, managing director of the Booksellers’ Association UK, believes that this is partly due to marketing techniques. “I think the e-book bubble has burst somewhat,”, she told CNBC in 2019, “sales are flattening off, I think the physical object is very appealing. Publishers are producing incredibly gorgeous books, so the cover designs are often gorgeous, they’re beautiful objects.”

The first eBook was created when the US Declaration of Independence was digitized by Project Gutenberg in 1971, the same year that the first email was ever sent. Almost fifty years later, there are over 6 million digital books available on the Amazon Kindle Store alone. A click and a swipe provide instant access, but that enchanting smell of paper, a pleasing blend of coffee, wood and vanilla is irreplaceable — at least for those of us who have bought into the sentimentality of paper. While statistics show that the majority of readers have not been lured entirely into the world of electronic books, younger generations may well develop a similar attachment to eBooks. Their convenience is undeniable; portability, immediacy and interactive features such as highlighting, font size and note taking. eBooks are generally cheaper than their physical counterparts and can often be easier to read, since print publishers often reduce font sizes to cut costs. According to Planet Blue at the University of Michigan, 8,333 sheets of paper can be produced from one tree, sparking the question of whether the environmental cost of traditional publishing is worth our love for paper books.

Audiobooks are another emerging strand of publishing, beginning in the 1930s when an American foundation for the blind designed programs for blind readers termed ‘talking books.’ The word ‘audiobook’ came into use in the 1970s when records were largely replaced by cassettes. Within the hecticness of modern life, finding an opportunity to read can prove difficult, so audiobooks provide an accessible alternative. Listening to an audiobook and reading a physical book are entirely different modes of consuming information, but the benefits of both are substantial. Of course, his difference is not an exact science and as a Forbes article found “Those who prefer one medium or the other simply like the feel of a physical book or the spoken kind.” Beth Rogowsky, associate professor of education at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania, wrote in Time Magazine that she always “viewed [audiobooks] as cheating,” a view shared by some readers who see audiobooks as a ‘shortcut’. However, after testing these assumptions in a 2016 study, “no significant differences in comprehension between reading, listening, or reading and listening simultaneously” was found. In a New York Times Opinion Piece, Daniel T. Willingham, a cognitive scientist, also came to the conclusion that listening to an audiobook is not “cheating” but wrote that “Our richest experiences will come not from treating print and audio interchangeably, but from understanding the differences between them and figuring out how to use them to our advantage.”

Audiobooks are a performance for the ear and pair well with autobiographies. Listening to autobiographies narrated by the author can feel like a very intimate experience, and give the impression that the story being told has been written just for you, a different kind of intimacy than physically holding a book in your hands. Words themselves have the power to create such intimacy, but when they are read to you by the author themselves, describing their own life, the connection can be even more profound. Michelle Obama’s Becoming is an exceptional read in its own right, but listening to Obama narrating her own story is truly an extraordinary way to experience the book. The narrator is an important feature of audiobooks: Audible’s sampling of audiobooks allows the listener to pick and choose their preferred reader. One popular Audible narrator is Stephen Fry, whose calm, soothing voice is the perfect bedtime storyteller. However, books like Bernadine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other do not lend themselves to audio. Evaristo dispenses of some of the conventions of punctuation, creating a flow which may be difficult to appreciate through the medium of sound alone. Many writers including James Frey and Ben Foster pitch themselves as their novels’ narrator. “There’s no denying that reading one’s own work can carry with it certain advantages,” stated Basil Sands, a self-published writer and actor stated in an Audible article, adding that “If it works, it is truly rewarding.” Book design is an art in itself, and for many writers page space, punctuation, and fonts are essential creative tools; for publishers, these print details are important marketing devices.

In such a hectic world, it is not surprising that some people favour a passive form of entertainment rather than reading in their downtime. For students, who spend as much time reading as they do breathing, the pleasure of reading can often be masked by heavy workloads consisting of reams of textbook notes and academic journals. Streaming services and social media are integral parts of daily life. Reading has never offered us more; an escape from the chaos and noise of the modern world. After years of leisure reading reaching all-time lows, there has been a surge in reading since the pandemic began with 35% of the world saying they were reading more. The availability of eBooks and audiobooks have made reading one of the unexpected silver linings of the pandemic. The benefits of books, whether read or listened to, cannot be underestimated, and now, we have more choice than ever of where and how we consume literature.

Image Credit: Maximilian Schönherr from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license.