Our favorite songs are fecund pleasures, increasing in affectivity and growing with us over time, like a reliable friendship. But, if you dilute the potency of a precious song through overuse, that is overuse without innovation, good songs get worn out. One of my fecund favorites, Max Richter’s “On the Nature of Daylight”, is dangerously close to becoming trite in this way, and it is lazy filmmaking that’s to blame.

(I’m betting that you’ll recognize it, but in case the name of the piece hasn’t rang any bells, go ahead and give it a listen here while you read on.

Now, it’s not unusual for certain inspired songs to earn places on a variety of movie soundtracks. In fact, songs like Lynard Skynard’s “Sweet Home Alabama”, Katrina and the Waves’ “Walking on Sunshine”, and James Brown’s “I Feel Good” frequently find themselves on lists of the most overused songs in film. As far as classical pieces go, loads of films capitalize off of audiences’ familiarity with Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” (most famously in Apocalypse Now) or Luigi Boccherini’s “Minuet” (usually used to make fun of classical music) But, these pieces are decades if not hundreds of years older than the cinematic medium itself and, like the pop songs, they already have distinct reputations.

What does constitute a unique phenomenon in film music history is the existence of a contemporary piece of classical music exerting such ubiquitous influence over the industry. It’s nearly unheard of and yet, that’s exactly the sort of hold Max Richter’s “On the Nature of Daylight” seems to have on modern film and television. Proving the point, at a pub quiz I attended last September there was a film music themed round where we had to say which movie certain music belonged to; bonus points were awarded if you could name the song itself. As expected, the round featured some well-known scores and a few pop songs, which were for the most part pretty easily identified, if not named. Still, when the soft postminimalist melody of “On the Nature of Daylight” began to swell in the air, I was surprised to see that the eyes of six members of my eight-person team lit up in recognition– three of them knew Richter’s work by name.

Most everyone knew the piece from its use as sonic bookends in Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival, but chances are most of us have heard it a number of times. “On the Nature of Daylight” also features in such films as Stranger than Fiction (2006), Shutter Island (2010), Disconnect (2012), the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi (2012), The Face of an Angel (2014), The Innocents (2016), and Togo (2019). In terms of television, the track also plays at the end of an episode of Hulu’s Castle Rock titled “The Queen”, and was used very recently in the 35th anniversary episode of Eastenders. Perhaps most tellingly of all, a music video for the song starring Elisabeth Moss was released in 2018. I ask you, reader, how many pieces of classical music get their own music video?

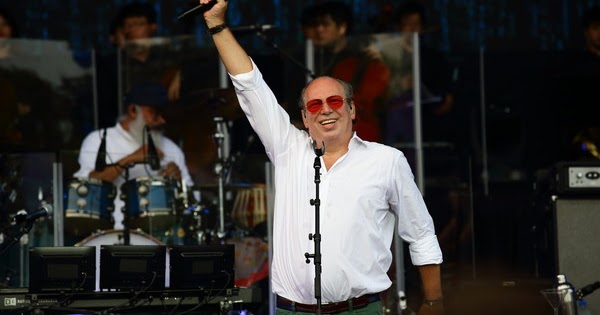

Now, Hans Zimmer performed at 2017’s Coachella, so in terms of high art mediums infiltrating pop culture spaces, stranger things have happened. But whereas Zimmer’s most famous music comes from the scores of popular multi-film franchises like Pirates of the Caribbean or The Dark Knight trilogy, Richter’s song wasn’t written for film at all, making its popularity even more startling. “On the Nature of Daylight” is the second track off of Richter’s 2004 album The Blue Notebooks, which the composer produced in the run-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq as a work of protest art. The album was a critical success, but certainly not a commercial one: Richter has even gone on record saying that he and his family were forced to leave their home due to poor album sales (https://www.popmatters.com/192773-max-richter-the-blue-notebooks-2495537909.html).

Thankfully, Max Richter is no longer an obscure musician, but the fact remains, the overuse of “On the Nature of Daylight” has become grating. One the one hand, I’m immensely happy to see a genre of music that typically carries connotations of elitism appreciated by such a wide and diverse audience. Moreover, as a fan, I’m delighted that Richter has become well-known and that his work has become lucrative. But, “On the Nature of Daylight” now has such a formidable cinematic reputation that I’ve begun to wish filmmakers would be a bit more discerning when selecting the track for use in one of their productions.

The song’s immaculate slow build, the melancholy of its minor keys, the exuberance of the string section at the song’s peak, all of this allows “On the Nature of Daylight” to lend poignant emotional resonance to any scene in which it’s used– at least the shadow of it. See, the trouble is, most productions don’t earn this payoff, and when the narrative reaches for a release it hasn’t earned, it cheapens an exceptionally potent piece of music. In fact, given the track’s popularity, its use can almost feel cliched, which is particularly damning for pieces like “On the Nature of Daylight” because it has no distinct pop culture reputation to fall back on outside of its use in the industry. This means that the industry has the power to ruin it, and as someone very much attached to this song, it’s hard to watch the movies bleed Richter’s work dry.

None of this is the composer’s fault; he has every right to grant the use of the song to paying production teams, but it’s a bad look for filmmakers who appear to be taking emotional shortcuts. Boring cinema gets made when filmmakers attempt to adhere to recipes for successful movies, instead of leaning into the spirit of innovation that birthed the medium in the first place. You don’t know what all you can do with a film until you try it and it works. “On the Nature of Daylight” worked in Arrival, and I actually think it works in a few things, but that doesn’t make the song a catch all for conveying melancholy every time a cinematic narrative calls for it.

So, I’m making a very serious, probably selfish, and likely ineffectual plea, that the film and television industry stop the use of “On the Nature of Daylight” in their productions. I realize making this request roughly translates into shouting “Hey, all of showbiz, stop ruining my favorite song!” into the void, but my personal taste and investment aside, the industry really would do well to go back to scoring films with specificity. It really is a beautiful thing when a score becomes synonymous with certain film visuals, forming an exclusive and symbiotic relationship. Plus, this method gave us Hans Zimmer shredding on the banjo in Coachella Valley, so there’s that.