PPE at Oxford is often seen as a one-way track to ending up in the House of Commons (usually on the wrong side of the house). Introduce yourself to anyone as a PPE-ist and you’ll inevitably receive the displeased sighs or disgusted face befitting the discovery of a bit of chewing gum on the bottom of a shoe. This is understandable, of course: many politicians do take PPE at Oxford and go on to make a mess of the country they were ostensibly taught how to govern. So perhaps this article is just a futile effort to avoid the unfortunate association of my degree.

However, believe it or not – and certainly don’t inform my politics tutor (sorry Federico) – over the last year or so I’ve found it impossible to engage with political news, especially British party politics. Whilst in Sixth Form I was one of those (super cool) people constantly refreshing Twitter to find out the latest fiscal announcement or policy U-turn, ironically enough, being in Oxford has slowly but surely reduced this desire to the point where I have to make an active effort to keep on top of what’s going on in the world. Recently I opened the Financial Times and was genuinely baffled by an editorial reading “Labour has shredded its claim to competence” – having missed all mention of the budget, an event which looms large in the calendars of political aficionados (and those who wish they were).

Perhaps this is simply because you naturally get sick of the subject you’re constantly studying – just look at the mockery English students face when they complain about having to read novels all day. No matter how much you might think you like something, subjecting it to endless academic scrutiny is a surefire way to prove yourself wrong. Yet this isn’t the case for me. Contrary to the beliefs of all those politicians-in-waiting, the academic politics course in Oxford is very far from lessons in governance; even less so is it training to be a backbencher (apart from induction into not having much real thinking to do). And the kinds of quantitative analysis and theory-testing that we do is, in fact, very enjoyable for me – precisely because it is so different from what you get in a current affairs programme.

The real explanation, I think, as to why getting through a news article feels like an ever more insuperable task, lies in a dangerous conjunction of four facts: (1) there’s not (that) much you can do to change things significantly; (2) many of us are fairly isolated from its fluctuations, or can at least pretend that we are; (3) politics is very boring; (4) Oxford is pretty interesting. I don’t intend to debate the first here: whilst lowering the voting age to 16 is a good step in giving younger people more of a voice, the overall nature of representative democracy means that individuals’ impacts are inherently minimal, so it takes some kind of aggregating movement to have a discernible effect on the composition of government. I hope for your sake, dear reader, that (4) is true – whether that’s because you have back-to-back nights out or because you get to have tutorials with academics you love, it seems fair to suggest that student life in Oxford is, on the whole, pretty damn good. With a huge range of events, societies, work, and interesting people, the usual problem is having too much, rather than not enough, to do.

If you are deeply exposed to the vicissitudes of short-term policy decisions, then naturally politics will be of some interest to you – even if not out of choice. And this is true for lots of students. Many people simply cannot afford (quite literally) not to pay attention to politics. Even if you aren’t allowed to work during term time, when the vacation rolls around again, you suddenly realise that someone has to pay for all those formals – and not everyone can pull out daddy’s chequebook. But still, if you aren’t dependent on the government for some kind of benefit, seeking refuge, or any number of other cases, it’s (all too) easy to pretend as though Westminster is far away. (Tuition fees? No such thing.)

If that’s not convincing – which it really shouldn’t be – then consider (3). Oxford’s own politics tutor Matt Williams is fond of describing politics as “Love Island with nukes”. This can be taken in two ways: if you love soaps and have little else going on in your life, then perhaps this high-stakes production will be just the opiate you need. Alternatively, if you wouldn’t watch Love Island even if held at gunpoint, it sounds like just another reason to clock out. With so much else going on, who in their right minds wants to follow a cabinet re-shuffle? That’s not helped, of course, by some of the least charismatic politicians ever to grace Parliament’s seats. (Say what you like about him, Tony Blair’s PMQs are some of the finest lessons in British debating you could ask for. His successors? Not so much.) When you stop to think about it, it’s almost amazing that so many people read about politics so frenetically. If you aren’t sure, I can recommend a hundred more enjoyable or interesting things to look at (Try Cherwell’s Lifestyle section).

To all of this you may well say: it might be just lovely for you to frolic around, blissfully unaware, in your ivory tower. But you have a duty to be informed, to participate in social and political affairs. In the past, I myself was one of those moralising evangelists for being an ‘active citizen’ – it was being informed or the guillotine. But Tim Harford, a staple of the centrist dads, makes a fair enough point: why? There’s certainly a level of knowledge and attention which you should pay to the goings-on in the world – these things do matter. You should vote and have opinions on who runs the country – god knows other people will if you don’t. But after a certain point, the marginal gains of another news story or six drop off rapidly. Who does it help? It might feel like doom-scrolling The Guardian is a necessary response, forced upon you by the wrongs of ‘the system’. But if you’re not organising a movement, attending a protest, door-knocking, or voting (none of which I intend to diminish in the least here), then why bother? At a certain point, following politics just doesn’t help.

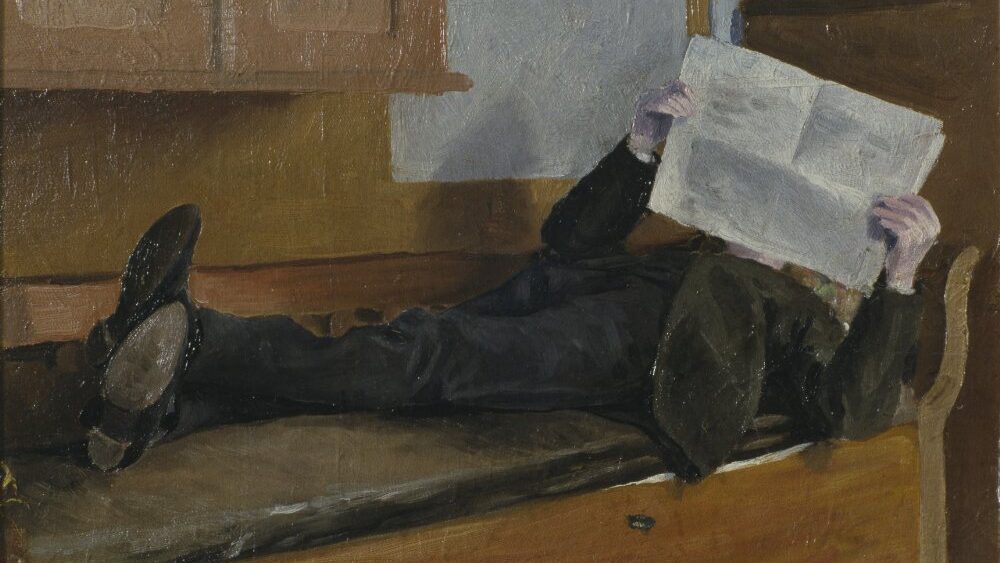

And whilst I wouldn’t want to suggest that my life in Oxford is making the country, let alone the world, directly better off, it’s too quick to just dismiss it. At the least, study gives you critical and (if you’re lucky) practical skills, and I think much more besides. After all, it is a luxury to be able to do this – to turn off the news and read a book, chat with others, and explore an ancient city. So make the most of it. You’ll have the rest of your life to follow Labour’s “shredded claim to competence”.