“Because it’s so much fun, Jan!” This was Quentin Tarantino’s answer when an interviewer asked him to justify on-screen violence. Few would disagree. From the thousands who flocked to see the on-stage strangling of the Duchess of Malfi in the early 1600s, to the 16.5 million moviegoers who paid to watch the slaughter of four teenagers in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), violence has always been a staple of popular entertainment. Even the supposedly buttoned-up Victorians had the sensational novel and the ‘penny dreadful’; The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde sold 40,000 copies in only six months.

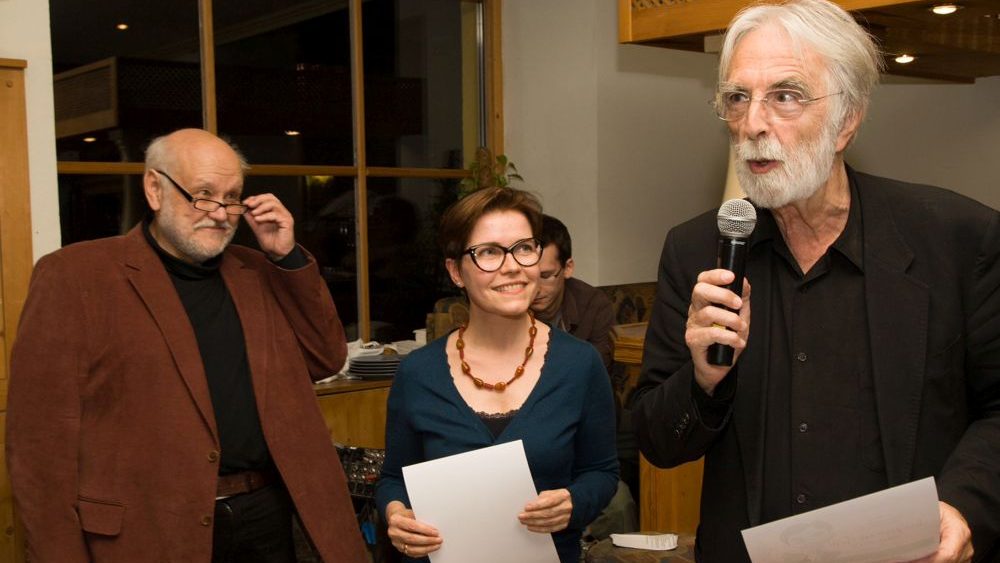

But is violent entertainment really just a bit of fun? Aristotle thought it might lead to spiritual renewal through catharsis. Psychologist Dolf Zillman thought violence was entertaining because it is perversely arousing. Others have likened it to a ‘forbidden fruit’ or as a contained rebellion against everyday morality. Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke, whose films The Piano Teacher (2001), Funny Games (1997), and Caché (2005) were re-released this summer, shows that violence in media isn’t harmless; it desensitises us to the act itself.

Haneke has made it his project to remove the fun from violence on screen. He wants to remind his viewer of what it means in real life. In a 2009 interview, he articulated the dangers of desensitisation: “I don’t notice it anymore” when violence is shown on the news. He told another interviewer that physical violence “makes me sick. It’s wrong to make it consumable as something fun”.

So his most violent films are anti-violence. They intend to be anti-entertainment, too. Funny Games (1997), for example, tells the story of a bourgeois family’s country holiday. Two young men take them hostage in their home, torturing and killing them in sadistic ‘games’. It’s a pretty standard sounding slasher plot, except that Haneke frustrates the viewer at every turn. When one of the young men is shot, the other one breaks the fourth wall, ‘winding back’ the plot with a TV remote: he frustrates the viewer in their desire for revenge. Even the violence avoids gory catharsis: the murder of the last remaining family member is an anticlimax, as the mother is quietly pushed off a boat to drown. Breaking the fourth wall, the villains mock the viewer’s appetite for entertainment. After beating a dog to death with a golf-club, one of them turns towards the camera and winks. Thus Haneke seeks to show our complicity (also the title of a recent retrospective) in the characters’ suffering.

Caché does the same. It begins as a surveillance thriller. A French TV host anonymously receives videotapes of his house: he is being watched. But the ‘whodunit’ setup never pays off. The film shifts its focus into an exposé of French colonial violence. We never discover for sure who sent the tapes. As in Funny Games, Haneke frustrates the viewer’s wish for a tense, violent thriller. A tale of bourgeois paranoia is trivial next to the mass, unthinking violence of colonial brutality.

However, I doubt cinema can ever truly offer a deconstruction of its own violence. Take, for example, the opening of Funny Games. A family drives down an idyllic country road, playing ‘guess the opera’. Suddenly the words FUNNY GAMES appear in huge blood-red letters, accompanied by the discordant screams of the avant-garde metal band Naked City. The noise verges on painful, but it’s so audaciously satirical that it’s also incredibly compelling. Haneke’s postmodern tricks do the same thing. The torturers break the fourth wall; they comment on their own violence; they compare themselves to ‘Tom and Jerry’ and ‘Beavis and Butthead’. All these make for bold, playful storytelling so strangely fascinating that it ends up aestheticising the violence Haneke wants to deplore. He cannot escape his own talent: by making a film so engaging, he fails to avoid the ‘fun’.

Caché also struggles to escape the conventional role of violence on film. The graphic suicide is there to shock viewers into recognising their own role in the erasure of colonial suffering. But it’s hard to separate the moral of the story from the form it takes. By shocking the viewer, the violence also keeps them watching. It feeds their hunger for suspense. A massive splash of blood across a white wall is so memorable, so artistic, so brutal, that it serves to satisfy the morbid desires of the desensitised movie-goer.

Haneke’s aims are didactic, but he carries them out with such bold style and biting satire that, for viewers already used to violence on film, it’s hard not to get something pleasurable from his bleak cinematic imaginarium. He may want to teach us about the dangerous power that violent entertainment offers. But he can never avoid an uncomfortable truth: that cinema, however upsetting, is always entertainment.