No one reads these days. If it’s longer than an Instagram caption, it’s not worth my time. I doubt most people will even make it to the end of this article. As more and more studies tracking the decline in literacy pile up, doom-mongering professors self-importantly shake their heads in despair that “people don’t read Joyce any more”. We fiddle on our iPhones while Arcadia burns.

This moral panic is nothing new. People have been murdering literature ever since its birth: the absence of the great Ancient Greek works from the Elizabethan school curriculum precluded the growth of tragedy; Victorian narrative serialisation killed long-form literature; and, worst of all, in the 18th century people stopped reading serious works because of the growing popularity of (god forbid) the novel.

It may be true that today’s attention economy is robbing us of the ability to engage with literary works in a meaningful way. But the ‘prophet of doom’ attitude assumed by those who claim intellectual distinction does more harm than good. The way we speak about reading sets us up for failure.

Reading is, and has long been, an essentially privileged activity. Quite apart from the financial burden, it requires the luxury of physical and mental leisure, scarce in the working world where every minute is monetised. The sheer number of books that everyone ‘must read’ makes it a daunting venture to even begin, especially for those for whom it has never been a priority.

Even self-proclaimed readers often harbour backwards attitudes. Reading is increasingly spoken of as a duty, as if, by reading Bleak House, you are selflessly engaging in a civilisation-saving act. Yet such an attitude merely perpetuates a utilitarian perspective that cannot, in any meaningful way, incorporate the delightfully useless. Literature has always been an effective cultural lightning rod. You don’t have to actually engage with it – as long as you can self-righteously lament that no one else is engaging with it, you can’t fail to sound intelligent. The practice is condensed into an aesthetic and fetishised – who cares if you didn’t understand Dostoevsky, as long as you can log it on your Goodreads?

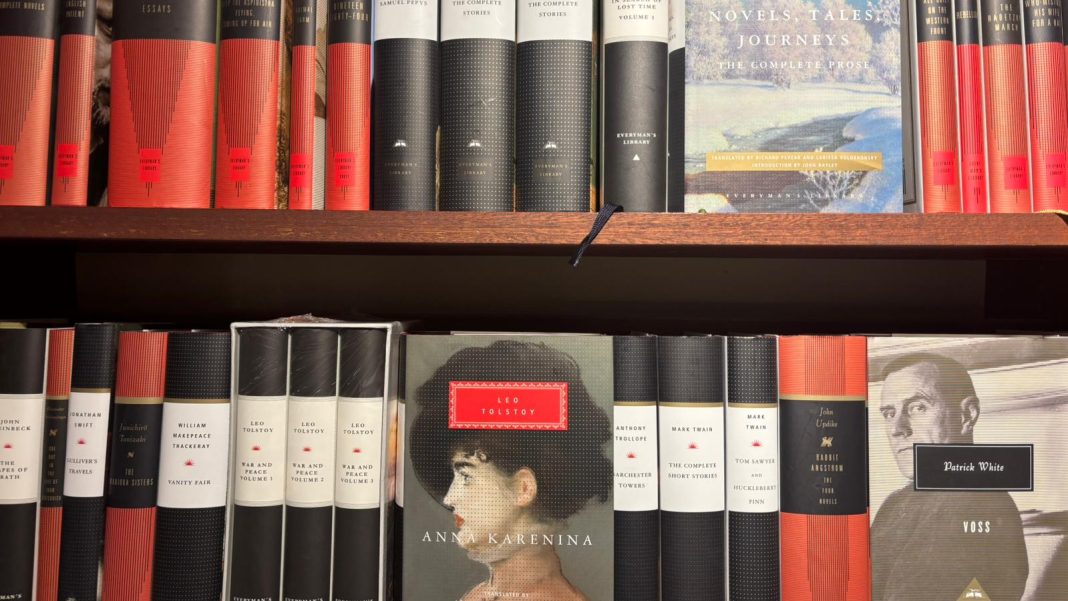

The issue is complicated by layers of literary discrimination. Not only are people not reading enough, but they are reading the wrong things, and, as a consequence of this vicious cycle, this means they will never be able to understand the right things. The phrase “the extinction of humanity” is bandied about at literary festivals, while connoisseurs clutch their copies of Tolstoy like a life raft that will save them from the tsunami of the ignorant masses. There’s something particularly jarring about hearing the privileged few bemoan, in their practised RP, the preference of the populace for ‘vulgar’ literature. Because, of course, it’s the craze for ‘romantasy’ books that will turn us all into mindless automatons. Unsurprisingly, this turns out to be yet another permutation of the class divide – snobbery marketed as philanthropic concern.

The ruthless taxonomy of books – differentiation by library sticker, by inclusion in the curriculum, by cultural consciousness – is inherently problematic. The notion of ‘the canon’ has often been questioned, yet it seems impossible to push back on the binary of classic literature and popular books. We live by an absurd metric whereby older is considered better – if telephones aren’t mentioned, it’s a ‘classic’ by default. We forget that Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories were considered pulp fiction when released, that Austen was disparaged for her frivolity. Lewis’ The Monk (1796), which occupies a secure position on the ‘Classic Literature’ shelf somewhere between Lawrence and Locke, narrates a story of pornographic revenge, stuffed with garish ghosts and crude sensationalism that would scandalise the Wattpad users of today. Clearly, the ‘popular’ and the ‘classic’ are not mutually exclusive labels.

Why should one form of literature claim the monopoly? Why is it that audiobooks, e-books, even films, are implicitly placed below physical books in the accepted hierarchy of media consumption? Literacy is not a necessary precondition of literature. Our current audiovisual culture encourages the dissemination of literature in different forms; media variation does not spell the death of literature. Reading is an activity that should not be limited to the physical action: it is a social, dialogic process. The canon cannot and should not sit there unmoving.

Of course, we should all read more. Of course, our attention spans are being threatened by the predominance of increasingly short-form, increasingly digital media. But these concerns are perennial, and performative hand-wringing will get us nowhere. Before we mourn the death of literature, let’s check its pulse first. See? I told you that you wouldn’t make it to the end.