With roughly 55% of the world’s population living in cities, the urban world – the brainchild of architects – has become what most people recognise as home. Studies have suggested that architecture has a direct impact on an individual’s mood, assigning it an emotive power analogous to art.

However, unlike poetry or painting, architecture cannot be entirely self-expressive or individualistic. Buildings are inherently public; they are designed to be used by others. At the same time, the choice of which buildings to create and which ones to tear down is an expression of that power. For example, during the Cultural Revolution in Beijing, 4,922 out of 6,843 officially designated places of cultural or historical interest were destroyed in an effort to rewrite history in line with contemporary political ideology. As unapologetically visible structures, buildings are the clearest expression of power and history we see in day-to-day life. Buildings have power – in defining which stories are told, in defining which spaces are available to whom, as repositories of history, as shapers of memories and mood. This is a power that purely functional entities, like a drain, or highly individualistic and expressive disciplines, like art, do not possess.

Art and function converge within architecture to reflect the attitudes and ideologies of the time. Neoclassical architecture heavily referenced ancient Greek and Roman motifs, from Ionic columns to direct depictions of the Classical world’s gods. Neoclassical architecture hit its height in popularity in 18th-19th century Europe, which overlapped with the Enlightenment. This movement emphasized symmetry and harmony, moving away from the ornate look of the preceding Baroque and Rococo periods, and arguably acting as a visual embodiment of the Enlightenment’s emphasis on order and rationality. Neoclassicism also overlapped with colonial expansion. Colonial architecture often incorporated aspects of neoclassicism, perhaps in an attempt to signal that they are the ‘new Roman empire’. These design choices reflected the discriminatory ideologies of the time, which associated Europe with reason and civilisation and the colonised with intellectual and cultural inferiority.

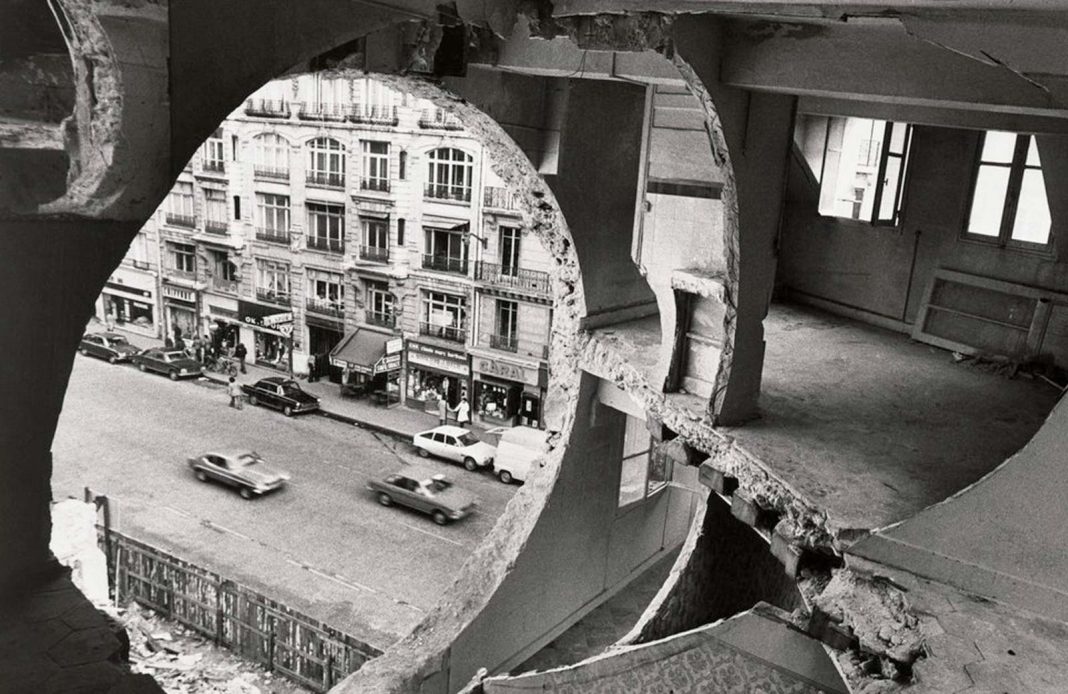

Another example of architecture capturing cultural attitudes is ‘anarchitecture’, in which the architectural structure itself becomes the art. In the 1970s, Gordon Matta-Clark exemplified this approach by drilling wall-sized circles into disused buildings to express his discontent with urban disrepair. Architecture can even comment on how humans relate to nature. For instance, the meticulously curated gardens of Versailles reflect humanity’s desire to control and dominate nature, while the Art Villas of Costa Rica are designed to blend into the greenery, emphasising its coexistence with the neighbouring rainforest. In these cases, architecture can crystallise the cultural attitudes and values of contemporary society. In this case, the relationship between art and function is symbiotic – art serves the function, the function feeds the art.

The relative lack of embellishment central to most modern (broadly speaking, post-WWII) architectural styles does not necessarily imply an artistic vacuum. In fact, functional designs can heighten the artistic presence of architecture. Shifts in longstanding power structures, such as the dismantling of the British Empire and technological advancements like the accessibility of photography pushed many art forms, from painting to film, toward the metaphysical.

The Barbican, for example, evokes the feeling of a fortress – imposing, impenetrable to outsiders, a city within a city – without being a pastiche of a fortress. Brutalist icons, like Balfron Tower in London and the Toblerone tower in Belgrade, have cemented their place in architectural history due to their distinctive silhouettes. The bare, unembellished nature of concrete creates a certain starkness that draws attention to the building’s composition and its relationship with light, absence, and presence. Through composition, shadow, and light, the artistic aspect of architecture extends far beyond embellishment. Functional design, then, can feed into the artistic presence of architecture.

Overall, architecture is both form and function; whether you think it’s more one or the other hinges on the present state, mood, and needs of the living. A cynic might say that today’s world is reliant on mass production where individuals own very little. Think, for instance, of the meteoric rise of subscription-based models and buy-now-pay-later programmes. This might be reflected in the often-complained-about homogeneity of some new buildings. An optimist might say that the homogeneity of architecture comes from a cultural shift: that identity and culture have moved from the tangible forms of buildings to the intangible forms like the internet, a sentiment similar to “the book will kill the building” found in The Hunchback of Notre Dame. One way or another, architecture has a unique power that rises beyond art and function, and is definitely not the sum of art and function playing tug-of-war against one another.