If you’ve been paying attention to fashion, culture, or the images plastering magazines and movies in the last few months, you’ll have noticed it already. Digicams hanging from wrists like accessories. Wired headphones peeking out of coat pockets. iPods, flip phones, scratched CDs, bulky MP3 players reappearing not as relics, but as aesthetic choices. The next trend, apparently, is “going analogue”.

Of course, no one means actually going analogue (at least not in the true sense of the word). Digital technology gives us speed, storage, and infinite access. But it has also reshaped how we pay attention to what we consume – and what we value. This isn’t a mass rejection of Wi-Fi or a return to VHS tapes and landlines. What’s being signalled instead is a desire for the feeling these things create: slowness, tactility, a sense of limitation. A softer relationship with technology that resists the hyper-optimised digital world. Like most trends, it’s framed visually first – grainy photos, boxy devices, imperfect sound– but beneath the aesthetic is something deeper.

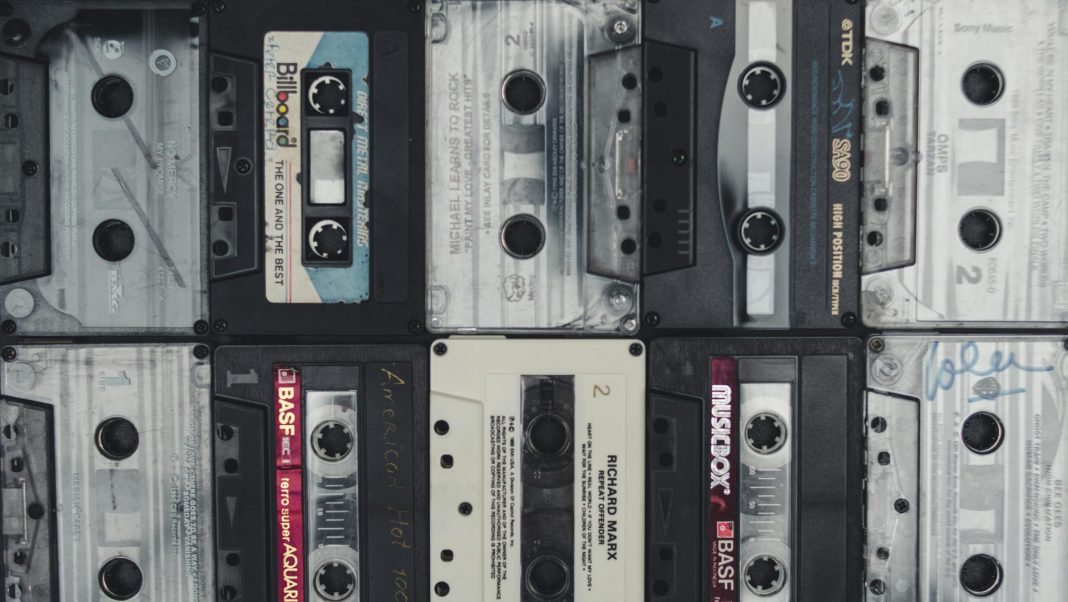

Growing up, physical media was never foreign to me. CDs and radios weren’t dusty objects belonging solely to my parents; they were part of my everyday life. There was something grounding about choosing a CD, placing it into a player, listening through an album without skipping every 30 seconds.

But as I got older, the internet pulled me away from that world. Not because CDs felt obsolete, but because digital platforms offered something intoxicating: freedom. The ability to explore entire genres, cultures, and scenes instantly. Spotify felt like liberation – an endless library that allowed me to build my taste without borders. I didn’t abandon my CDs; I was drawn outward by possibility.

That balance shifted when I got to university. Time pressure changed everything. Between lectures, deadlines, and constant low-level exhaustion, convenience became king. Spotify began to compete with my CD collection in a way it never had before. Streaming won, not because it was better, but because it was faster. Music slipped into the background, filling silence while I walked between buildings or ate rushed lunches.

For a long time, the tension sat quietly at the back of my mind. I could feel that something in my relationship with music had shifted, but it remained vague, easy to ignore. I kept listening, kept saving songs, kept letting sound fill the gaps of my day.

Suddenly, the way I consumed music felt uncomfortably familiar. It mirrored how I scrolled through Reels or Shorts: fast, fragmented, disposable. My 100-hour “liked songs” playlist had swallowed thousands of hours of artistic labour, compressing it into background noise I barely registered.

What had once felt like liberation was exposed as false freedom: infinite choice repackaged by corporations into content streams optimised for algorithms, convenience, and profit. Albums and artists were flattened, and music – something I had once approached with curiosity and care – had become a filler. I wanted to slow down, to choose deliberately, to listen with intention again. I didn’t want to consume – I wanted to curate.

So, I dug out my old MP3 player. It had survived several failed attempts by a younger version of me to make it ‘cooler’. Its final form was a black case painted over with green nail polish and finished with a craft-pen-silver-trim. I started downloading music again. One album at a time. Choosing carefully. Listening fully.

This is where the distinction between consumption and curation becomes clear. In the last few years, minimalism encouraged us to shed physical possessions for the sake of simplicity – books replaced by e-readers, DVDs by Netflix, CDs by Spotify. But in exchanging objects for platforms, we inherited a different kind of excess. Subscriptions multiplied. Notifications accumulated. The clutter didn’t disappear; it just became invisible.

A consumer scrolls, absorbs, forgets. A curator chooses, maintains, and returns. Analogue systems naturally demand this care because they are finite. You can’t own infinite CDs. You can’t skip through every song ever recorded in seconds. Limitation, I realised, isn’t a flaw – it’s what makes engagement possible in the first place.

This logic doesn’t stop with music. Increasingly, news, political ideas, and cultural debates are encountered the same way songs are: through feeds, snippets, autoplay. Social media is now where many people learn what’s happening in the world. When information is delivered through systems designed to maximise engagement, we stop seeking it out and start absorbing whatever surfaces first.

Here, the difference between consumer and curator becomes more than a matter of taste – it becomes a matter of thought. Passive consumption is no longer harmless. Algorithms reward speed, outrage, and familiarity, not nuance or reflection. Over time, this flattens discourse and erodes our ability to think critically. When corporations quietly decide what we see, what repeats, and what disappears, control over ideas shifts away from people and into profit-driven systems.

As “going analogue” re-emerges as a cultural moment, I hope it’s more than surface-level-nostalgia dressed up as style. There’s irony in a trend that seeks to reduce consumption, eventually becoming another thing to consume, but that irony may be unavoidable. Even so, the impulse behind it feels sincere: a collective longing to slow down, to feel friction again, to resist the constant pull of the next thing.

That desire has reshaped how I move through online spaces, too. Not by abandoning them entirely, but by treating them with the same intention I relearned through music. Just as I chose albums over playlists, I stripped platforms back to their essentials – turning YouTube into a long-form-content library by removing Shorts, letting Instagram exist primarily as a place for messages rather than endless scroll. These weren’t grand gestures or declarations of disconnection, just small acts of resistance against systems built to dissolve attention.

In that sense, “going analogue” isn’t really about objects at all. It’s about boundaries. About deciding where attention begins and ends. Whether this impulse lasts or is eventually folded back into consumption is still uncertain. But even a brief return to deliberate use – a pause inside a culture built on infinite access – feels quietly radical.