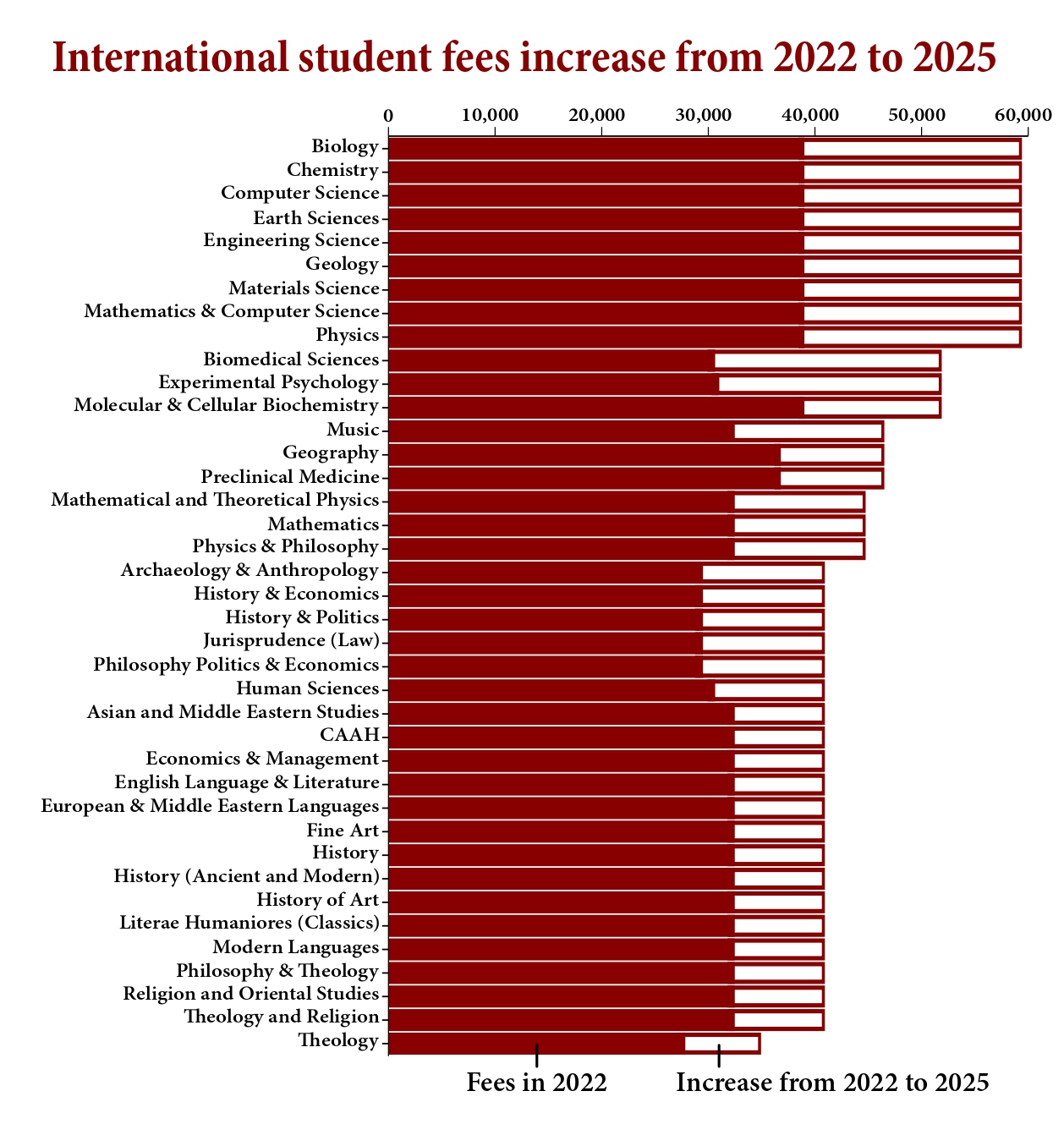

Overseas student fees have increased more than 37% over the last three years, a Cherwell investigation has found. BA Biomedical Sciences and BA Psychology have seen the biggest increase at 69% and 67% respectively. But even those rises do not make them the priciest degrees. In the Sciences Division, most degrees now charge £59,260 per year as of 2025/26 for overseas undergraduates, compared with the £9,535 cap for home students. In other words, an international science student can be paying roughly six times what a British counterpart pays for the same lectures, labs, and exams. These figures were obtained from publicly available information and through a Freedom of Information Request.

Broken down by division, the steepest increases are in science and medical subjects. In the Mathematical, Physical and Life Sciences Division, 23 degrees have risen by an average of about 47% over 3 years. 15 programmes have increased from £39,010 in 2022 to £59,260 in 2025, while the remaining 8 have moved to £44,880. Courses in the Medical Sciences Division, including Biomedical Sciences, Experimental Psychology, and Psychology, Philosophy and Linguistics, record the highest average increase at around 53%, driven by BA Biomedical Sciences and BA Experimental Psychology, which have jumped from just over £30,000 to £51,880.

STEM vs. Humanities

By contrast, Humanities and Social Sciences courses are tightly clustered around £41,130 for 2025: 27 humanities and eight social-science degrees move up from either £29,500 or £32,480, producing more moderate average increases of about 27% and 36% respectively.

Although tuition fees for domestic students are capped by the government at £9,535 – a figure that is now set to rise with inflation from next year – universities are largely free to set their own charges for overseas students. The home-fee cap was effectively frozen in cash terms for most of the last decade. Since 2012 it has only risen once, from £9,000 to £9,250 in 2017, before being nudged up again from 2025.

International origins

Over a period of high inflation, that has translated into a substantial real-terms cut in income per home student. Since Brexit, “overseas” has also included most students from the EEA and Switzerland who do not have settled or pre-settled status under the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement, meaning many EU students who would once have paid the home rate and accessed UK loans are now treated as full-fee internationals.

Unlike their American counterparts, it remains highly unusual for British universities to offer scholarships or bursaries to overseas undergraduates that cover a substantial proportion of tuition fees or living costs. In the United States, around 20% of international students receive some form of student loans. In the UK, overseas students are not eligible for loans from the Student Loans Company, and students at Oxford must complete a financial declaration which demonstrates their ability to pay their fees before they are finally admitted.

A handful of high-profile, highly competitive schemes – such as Reach Oxford or country-specific awards – exist, but they reach only a tiny fraction of the international cohort. Cherwell estimates that fewer than 30 of these places are available. For most overseas students, the sticker price is broadly what is paid. In practice, this means international undergraduates are funding their degrees out of family resources, private or government sponsorship, or commercial loans.

At the same time, the government has tightened rules on international students. Dependants have been largely removed from the student route, financial and English-language thresholds have been raised, and ministers have repeatedly stated that international recruitment needs to be “curbed”. These moves are justified by reference to data showing that a non-trivial number of people who entered on study visas later claimed asylum.

National problem

Universities across the UK are, by the sector’s own admission, in serious financial trouble. Because the home-fee cap was frozen for so long, teaching a home undergraduate, especially in a lab-based subject, now often costs much more than the regulated fee brings in. The Guardian reported back in 2022 that Russell Group universities make “a loss of £1,750 a year teaching each home student”. The effects are now clear: courses closed because of finances, departments merged or hollowed out, staff made redundant, and institutions in the regions openly talking about insolvency.

At the University of Cambridge, most STEM degrees cost £44,214 – around 25% less than Oxford – while Humanities and Social Sciences remain broadly comparable at £29,052. Cambridge’s Medical Sciences stand out at £70,554, one of the highest fees in the country. By contrast, University College London offers STEM degrees at £36,500 and humanities at £29,800, closely aligned with the University of Edinburgh, where STEM tuition is £36,800 and humanities £28,000.

Oxford and Cambridge Universities are often presented as exceptions, insulated by their large endowments and research income. To some extent, that characterisation is accurate: both institutions have kept the proportion of overseas undergraduates relatively stable, while many other universities have shifted much more aggressively towards international recruitment. The fee rises at Oxford indicate that these institutions are also operating within the same financial constraints that affect the wider sector.

The University of Oxford was approached for comment.