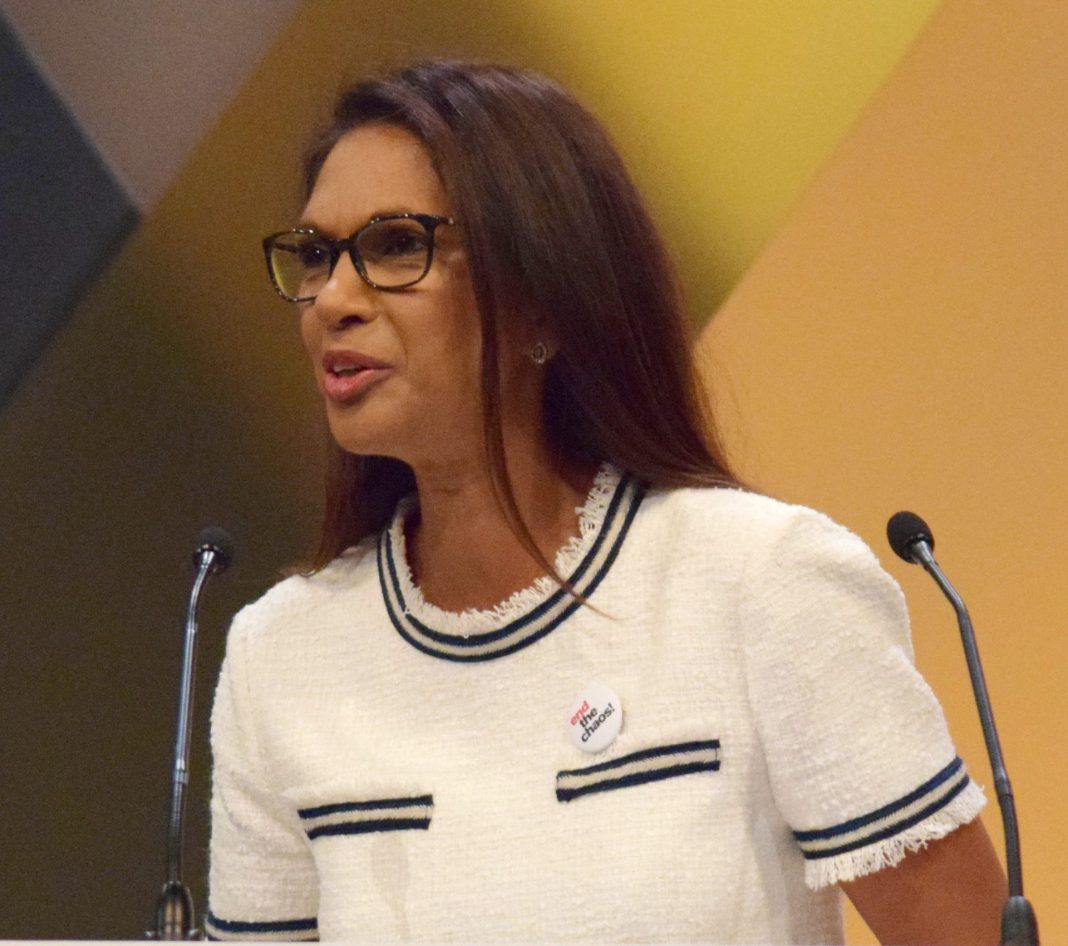

Gina Miller is not a conventional political figure. She did not rise through party ranks, but she has altered the British constitution twice – first by forcing Parliament to vote before triggering Article 50, as part of the Brexit process, and then by blocking the unlawful prorogation of Parliament by Boris Johnson in 2019. These interventions were clearly not about winning power, but about reminding the country that in a democracy, watching the watchers is everyone’s job. “Vigilance is a civic duty for all of us”, she says – a line that clearly sits at the centre of everything that follows.

She speaks about her court victories with a level of clarity that leaves little room for sentiment. They were necessary because the people paid to guard the system failed to do so. She’s blunt about it: the cases revealed exactly how easily a government can attempt to bypass Parliament – and how MPs often allow it. Her interventions filled a vacuum that existed only because, as she puts it, MPs had abandoned their basic duty to hold the government to account.

But Miller’s scrutiny of executive power didn’t begin with Brexit. People may think she “cropped up from nowhere”, she says, but her political awakening came during the Iraq War, when she first realised how heavily modern governments rely on archaic parliamentary tools. During the Blair decade, 98% of new laws were made through secondary legislation – procedures that cut down debate time in Parliament and often weaken scrutiny. Watching Blair repeatedly lean on these historic mechanisms (the so-called Henry VIII powers) lodged something in her: the sense that our constitutional culture runs on trust, tradition, and assumption rather than real constraint. Her assessment now is stark: “when there is a majority government, we almost have a state of autocracy.”

It’s why she sees 2016 not only as a moment of political upheaval but as constitutional exposure: “2016 will go down, I believe, in history as a really pivotal time for our democracy and our politics in this country…the change started, where we are now living and where we will go in the future.” Brexit revealed how poorly understood the system is, how quickly misinformation fills the gaps, and how fragile democratic checks become when voters – and their representatives – look away. When she says democratic norms are “under threat”, she’s not referring to party politics but the machinery beneath it: scrutiny, transparency, parliamentary literacy. In her view, the foundations have not adapted to the weight now placed upon them.

The examples she gives are, quite frankly, astonishing. The Brexit impact assessments – legally required, politically essential – were handled with a secrecy she still finds extraordinary. Parliamentarians were shown them in a controlled room, for a single day, without access to their devices. Only 83, out of 1450, bothered to go in. Worse still, the assessments themselves amounted to barely a few pages – including for sectors like the NHS and education – compiled last minute by David Davis, then Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union. For Miller, it’s symptomatic of a Parliament that has stopped taking itself seriously. The problem, she implies, is not that the public has lost trust – it’s that Parliament has stopped earning it.

This is what drives her belief that the system is outdated and needs structural change. When I ask how she would modernise Parliament, her answer is immediate: abolish the whips. I’m not convinced – the prospect of Parliament without any collective discipline feels, at least, dangerously unpredictable – but she is emphatic in her reasoning. She talks about the whipping system as “official bullying”, a mechanism that protects party leadership rather than the public. MPs, she argues, should answer to their constituents, not internal enforcers. Another reform, with which I wholeheartedly agree, is a statutory duty of candour in public life. This is something that, she notes, somehow doesn’t exist despite being fundamental in every other profession.

Miller is equally direct about the personal cost of taking such positions so publicly. “Being a woman, especially a woman of colour, has amplified the backlash” – not self-pity, but instead an explanation of the political climate she is working within. She describes the threats and misogynistic and racist abuse she receives as “incredibly difficult”, yet she refuses to frame them as a deterrent. Instead, they’re a motivator – she emphasises this sort of trained steadiness. “I’ve built the resilience to stand firm”, she says, less like a confession but instead simply as a practical requirement of the job. These attacks haven’t softened her but sharpened her. She refuses to cede the political ground to people who weaponise hate, and she refuses to let them shape the atmosphere of political life; even as she admits that the growth of the far-right has increasingly meant that whilst “there are always voices of hate and dissent and division in society, they have tended to be on the fringes, now they’re being given the permission and the oxygen to be mainstream and take over”.

Her assessment of the state of women in Britain is equally unvarnished. She sees a rollback underway – in workplaces, in culture, in politics – and she doesn’t bother dressing it up. Progress is not guaranteed; it can be reversed, and in her view, it is. She is clearly frustrated when she says that “my sisterhood and I, the things we fought for 30 plus years ago, we did not think we’d still be fighting for now in our places of work, in the home and in society”. She warns about the resurgence of traditionalist narratives around women’s roles with a seriousness that comes not from alarmism, but from this pattern recognition that can only come from experience.

Her understanding of fairness also comes from lived experience, but she describes it without sentimentality. She notices injustice because she always has; she acts on it because, as she describes, that is the only rational response. What grounds her now in this fight against injustice is simple: democracy is only as strong as the people paying attention to it. Institutions can be ignored; rights can be diluted; the public can become distracted. The remedy, in her view, is not submission to the system but scrutiny – the kind that is active, informed, and unafraid of confrontation.

Her advice for young women is correspondingly practical. Stop apologising. Use your voice. Don’t crave certainty. And recognise that campaigns, and working for what you believe in, require unglamorous, consistent work. These are clearly her tools for survival.

Similarly, when she says that “vigilance is a civic duty for all of us”, it is not with hope or idealism or sentiment. It is said with the plain confidence of someone who has seen what happens when people stop watching – and who has no intention of doing so herself.