Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has long proved an endless source of inspiration to illustrators. Hundreds of artists have illuminated Lewis Carroll’s vision, with many viewing it as the crowning jewel of their illustrative achievements. Alice is a story more preoccupied with posing questions than providing answers: on its publication in 1865, Carroll broke away from the tradition of didactic children’s literature, instead gifting us with an endlessly imaginative realm of wonderment. It is Wonderland’s enigmatic nature that has allowed artists the liberty to creatively re-interpret its landscape and characters, whilst drawing inspiration from their predecessors.

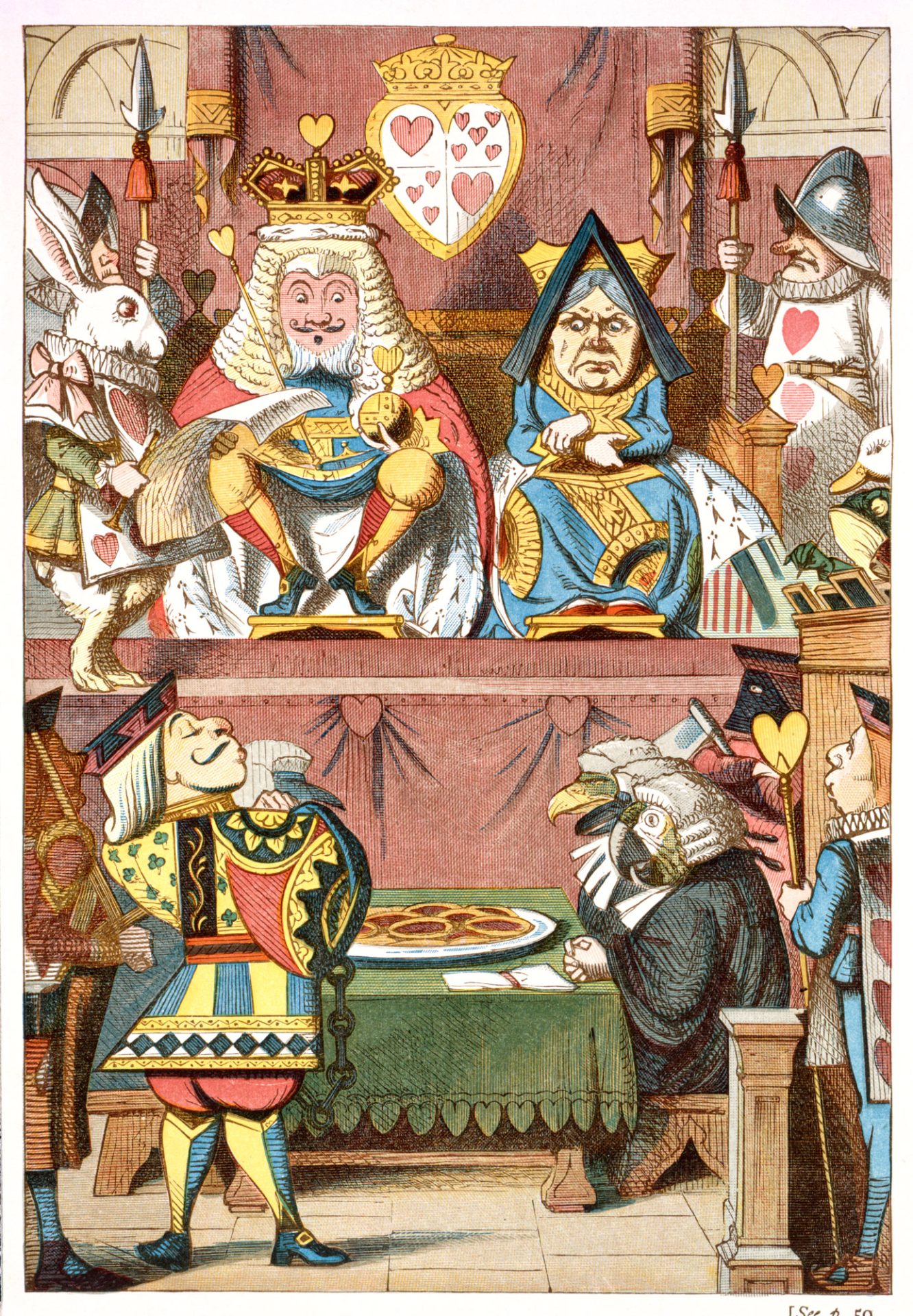

Though Lewis Carroll himself was the first to illustrate Alice in Wonderland, it was John Tenniel, a political cartoonist for the magazine Punch, who was chosen to illustrate the text in print. Tenniel developed his theatrical style through observing both zoo animals and actors on stage, which proved to be an excellent training for Wonderland’s cast of anthropomorphic characters. One of his most celebrated illustrations is that of the White Rabbit looking at his pocket watch. Tenniel’s Rabbit is both anatomically accurate and incredibly individualistic – his expression of timidity and apprehension humanises the character and renders the tardy Rabbit believable to his young audience.

Tenniel established the key tenet of illustrating Wonderland as being doubly fantastical, and eerily close to reality. Elements of Oxford life seem to have inspired him – the White Rabbit, with his checkered coat and pocket watch, is reminiscent of contemporary dons. The Queen of Hearts’ banquet, high table and gowns included, is akin to a formal. This verisimilitude recalls the most intriguing question of the book – how real is Wonderland, and how much of it is composed from real elements of Alice’s (or our own) lives?

Though Tenniel’s illustrations are undoubtedly iconic, many other artists have created novel oeuvres from Carroll’s classic. The first American edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was printed in 1899 and illustrated by Blanche McManus. Her illustrations are charming with their firmly American essence. The red, green, and black colour palette lends Wonderland a kitsch feel, evoking the illustrations of Dr Seuss. McManus’s Alice is rendered more cherubic than Tenniel’s slightly sour little girl. She fashions Alice in a full 1860s-style skirt and gives her round cheeks and soft curls to match.

Some of the most visually striking and beautiful illustrations of Alice in Wonderland came after the Second World War. Leonard Weisgard’s 1949 illustrations are stunning in their vibrancy and geometric patterns. Far more static than Tenniel’s images, they function as set pieces which expand our conception of Wonderland and its flora and fauna. Alice and her cat gaze at us pensively from the topsy turvy splendour of flowers, creatures, and chess pieces.

The decade of psychedelics, the 1960s, proved fertile to the imagination of Alice illustrators. One such was Tove Jansson, the Finnish author best known for creating the Moomin books. Despite the delicate touch and pastel colours of her illustrations for the Swedish edition, Jansson nevertheless maintains a more sombre, contemplative tone than her predecessors. Instead of the Cheshire Cat’s leering grin, we see the back of his head as he turns towards a pensive Alice, who is demurely clad in white.

Salvador Dalí’s 1969 photogravures of Alice in Wonderland are typically abstract. Dalí maximises his medium (which combines the processes of etching and photography), using it to highlight the book’s eerie blend of the imaginary and the real. In The Pool of Tears, Alice’s tears take on a life of their own, seeming to swim across a muted palette of blues, greens and purples. Alice herself becomes a tiny, shadowy figure, relegated to a corner; Dalí challenges the predominance of Alice in her own story. Wonderland mightily dwarfs Alice and the reader, who is her double and fellow initiate in this new realm.

Chris Riddell credits the original Alice pictures with sparking his passion for illustration. In his recognisable style of bright, primary colours (that emphasise a sense of childlike wonderment) Riddell pays homage to Tenniel in his 2020 illustrations. His protagonist takes inspiration from the real-life inspiration for Alice, Alice Liddell, and his Mad Hatter becomes an androgynous figure. This androgyny fits the enigma of Wonderland, which after all is a place where rules may be broken – why shouldn’t this include the binaries of gender?

Riddell’s approach to the Mad Hatter highlights what makes Alice in Wonderland so unique, as each generation of artists can adapt the story anew. Some past illustrations now seem delightfully anachronistic – take Willy Pogany’s 1920s flapper-style or Helen Oxenbury’s trainer-clad Alice for example. The ingenuity of Carroll’s textual creation birthed an expansive space for illustrators to explore their craft, and it is thanks to him and the work of Tenniel, whose iconic artwork has inspired countless others, that the momentum for Alice illustrations has not decreased since its publication.