Walking around Oxford you often feel like you’re part of the city’s tourist attraction. The long walk up to the Radcliffe Camera entrance, pushing the heavy door to enter your college: there’s always an eerie feeling of being watched. The feeling is right, you are always observed. Not necessarily by other people, but certainly by the myriad of statues, gargoyles, and grotesques throughout Oxford’s architecture. Many statues represent benefactors or founders of colleges, like in the case of The Queen’s College. Other common symbols are saints, like St. John in the tower of St John’s College. Oxford’s architecture is a controversial part of student life, considering the protests against Oriel College’s Rhodes Statue in 2020, or the architectural inequalities between ancient and modern colleges.

Modern perceptions of such decorations as wasteful expense ignores their important influence on college culture as well as identity. Sometimes looking up at new figures, ideas and bizarre statues can change our perspective on our environment. As we oppose statues that do not represent our values as an academic community–it can also be a fun exercise to examine what other figures dot our college rooftops.

If you’ve ever gone to the fifth floor of the Weston Library, or looked up during Matriculation, you’ll spot the statues atop the Clarendon Building. With some of them under maintenance, the building usually features the nine muses. A glance up when walking down Broad Street introduces you to the particularly striking Melpomene, the muse of tragedy, holding out her mask in a foreboding sign of how you’re about to do in your exams if you haven’t been revising.

For a more shocking experience, don’t miss Antony Gormley’s Another Time II of a nude man atop Blackwell’s gazing down on the tourist packed Broad Street. Its near human silhouette often catches the unaware mind. Exeter College seemingly prides itself on its unique acquisition that contrasts the classical sculptures atop Trinity College across the street. What’s better than a bit of college rivalry expressed through statues?

Oxford’s tradition of the bizarre figures continues further down Broad Street. Right beside the nude man, you have the mysterious Sheldonian Emperors, always a favourite for a bizarre tourist photo. They are centuries old with little documented reason for their creation.

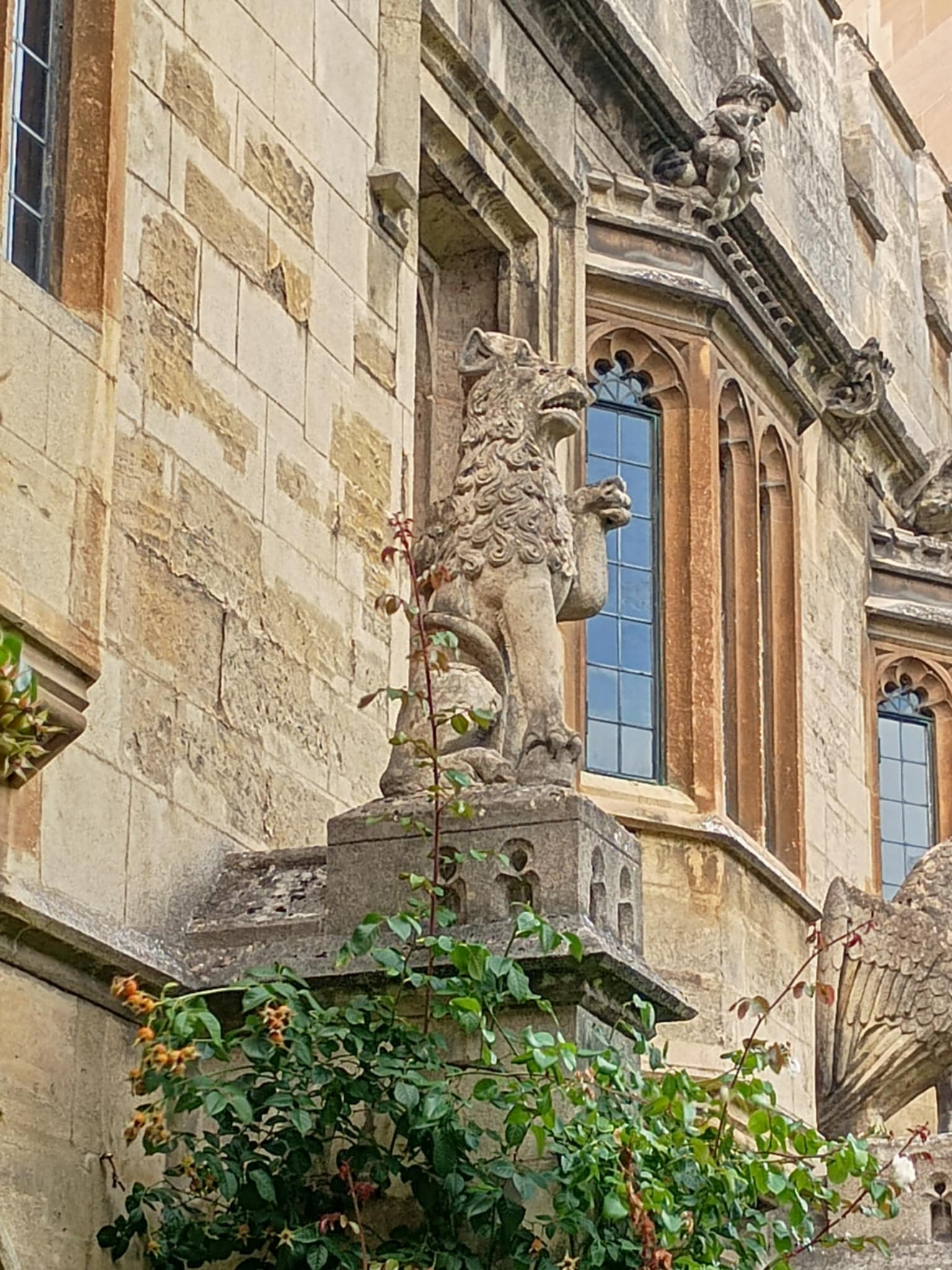

To move from their gigantism to the miniature, St John’s boasts an impressive collection of grotesques (small figures without a drainage or water use) in its baroque Canterbury Quad. With each new President being given the right to choose a figure of their choice, it features depictions of the Green Man, eagles, lizards, Kings, dragons, and a variety of crest-bearing angels. It also boasts some rare gargoyles on its neo-Gothic walls.

Oxford rooftops are a place for colleges to show off their learning and development. Trinity College chapel has four women, each representing Astronomy, Theology, Medicine, and Geometry. St John’s similarly features busts of the seven liberal arts alongside the seven virtues on either side of its quad.

Looking up reminds us that these are not simply pretty constructions for colleges, but they are sets of symbols and messages to undergraduates. Statues are not just entertainment, they have always been created with key values. The gothic and neo-gothic styles emphasised instruction as well as decoration. Magdalen’s medieval cloisters feature an eclectic set of imagery with statues representing everything from drunkenness to lust. In each corner there are the four medieval professions for graduates: a priest, a teacher, a doctor, and a lawyer. There are also statues of greed and fraud, warning undergraduates what to avoid, while also informing them of their ideals and future. Always ask yourself, what are you looking up to? Literally and metaphorically.

Many of these statues and figures will become staples of your college tours, or photos. Learning your surroundings, what they represent, and what their intention was, is always a fruitful way of understanding the past.