Every morning on my way to college, I pass through the cobblestoned, crowded St Mary’s Passage, overhearing stories of Oxford’s most famous literary duo, C.S Lewis and J.R.R Tolkien. It begins with the famed ‘Narnia’ door, said to have inspired Lewis’s magical wardrobe, followed by the soaring spires of All Souls College, the apparent influence behind Tolkien’s The Two Towers. Both men are woven inextricably into Oxford’s cultural and physical landscape. From parks, nature reserves, and pubs, to walking tours and guided museum visits: their presence is permanent and pervasive.

Other Oxford authors are similarly memorialised. In the dining hall of my own college, Brasenose, I eat my hash browns and baked beans beneath the gaze of Nobel Laureate William Golding. Outside, Lewis Carroll enthusiasts tour past the sign on Folly Bridge to the Perch in Port Meadow and the iconic Alice gift shop. And as I walk through the majestic grounds of the deer park, it is hard not to recall Oscar Wilde’s Magdalen Walks, written during his years of study here.

And yet, the conspicuous absence of women writers in the everyday geography of Oxford lingers. This year, I attended a creative writing seminar organised by the Careers Service, where the audience was asked to name authors from Oxford, and the room was buzzing with answers. No women authors were named. Visibility in public spaces shapes public memory, and Tolkien, C S Lewis, and Lewis Carroll enjoy an extended literary afterlife that has not been granted to the city’s women writers. The question persists: why are they missing from the town’s everyday lore and landmarks?

The simple answer is, of course, that women were only recently admitted to the University. The other common answer is that the male writers are ‘more famous’. But literary fame, as we know, is hardly ever neutral and is pervasively shaped by class, race, gender, and access to cultural capital. From their exclusion from university spaces, powerfully addressed in Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, to their marginalisation by critical scholarship until well into the 20th century, women have been systematically written out of Oxford’s cultural memory.

And if conditions for creative production were systematically denied to women within the lecture rooms and dining halls of colleges, the extended geography of the city, comprising pubs, taverns, and salons, accentuates this academic exclusion. The latter are sites of intellectual rendezvous and cerebral fraternising; the catalyst behind male scholarly camaraderie. Graham Greene spent his student days at the Lamb and Flag, the pub across from the Tolkien-Lewis haunt, Eagle and Child. Evelyn Waugh, whose novels draw from his days at Oxford, regularly drank at the Abingdon Arms, and spent his student years at the Oxford Union, drawing on his experiences at the Union in Brideshead Revisited. When he was a member, the Union had yet to open its doors for women, who were only admitted in 1963 after multiple failed motions in the previous decades.

Even celebrated men did not all have homogeneous access to power or cultural acceptance in Oxford. William Golding never felt a sense of belonging here, owing to his working-class background. Percy Bysshe Shelley was expelled from University College for his radical pamphlet defending atheism. Oscar Wilde was persecuted for his homosexuality and eventually imprisoned. However, individual hardships notwithstanding, they still moved through spaces that systematically excluded women. They could write in pubs and inns, mingle in debating circuits, hold fellowships, and return as commemorated alumni. Their gender afforded them access to an intellectual and cultural life that allowed for rebellion and resistance to be enacted within the very spaces that may have felt repressive.

While men are remembered in colleges, parks, and pubs – the visibly celebrated spaces – women tend to appear in the margins. Opposite the grand gates of historic Christ Church College lies the narrow, honey-coloured Brewer Street, where Dorothy Sayers once lived. Only a plaque by a blue door informs the passerby that she was a resident here. Iris Murdoch lived farther away, in Summertown, a residential part of the city. The commemorative plaque is obscured by an overgrown hedge, perhaps reiterating a metaphorical effacement. Somewhere between these two lies the cream-coloured house of philosopher and friend of Murdoch’s, Philippa Foot, located among a row of otherwise indistinguishable homes.

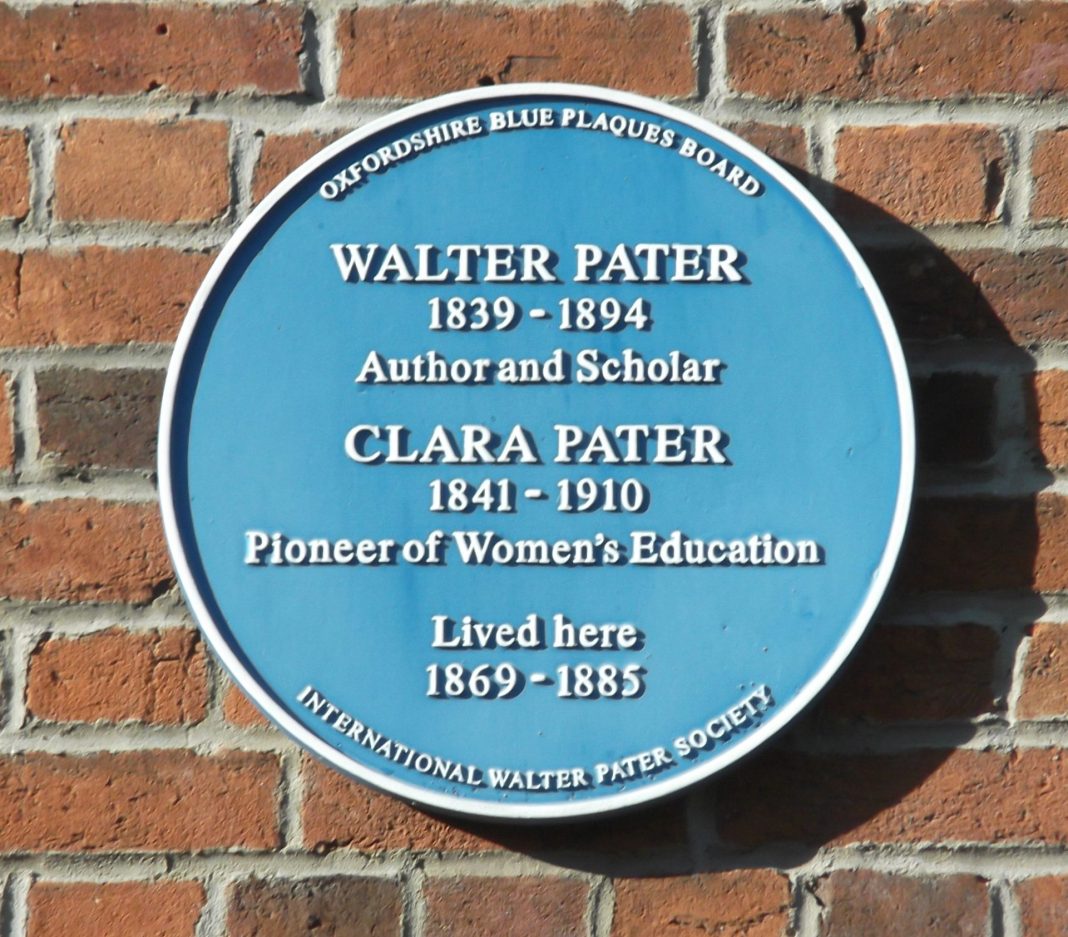

Not only are women’s absences striking, but also the ways their presence is actively recorded. The shared commemorative plaque for scholarly siblings Clara and Walter Pater is an example. It reads: “Clara Pater, pioneer of women’s education, and Walter Pater, author and scholar.” Both lived and worked in Oxford as scholars. Clara taught Latin, Greek and German, but their shared memory nonetheless enforces a subtle hierarchy.

And then there are the ‘muses’, the women who inspired the creative and artistic output of men whilst remaining underwritten in the city’s history. The presence of Jane Burden, Pre-Raphaelite muse to Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the wife of William Morris, is marked by a plaque, tucked away in St Helen’s Passage. Alice Liddell, the real-life Alice of Wonderland fame, lives on through Carroll’s stories, but also in the physical geography of Oxford: a wooden door depicting the patron saint of Oxford, Frideswide, placed at a Church quite out of sight in Botley, is said to have been carved by Alice.

If there are muses whom we recollect through male association, there are women who cannot be traced at all. Their presence in the city was liminal and remains undocumented, their access to intellectual life filtered through the domestic sphere. One of the earliest such women is Alicia D’Anvers. The daughter of a ‘beadle of civil law’ and first chief printer of the University, Samuel Clarke, she penned satirical verse about Oxford colleges and condescending scholars in her Academia, or, The Humours of the University of Oxford (1691).

Inside Oxford’s former women’s colleges, the traces are more deliberate and thoughtful. Somerville College takes pride in celebrating the women associated with it and is the only college with women’s portraits adorning its hall and chapel, Dorothy Sayers and Vera Brittain among them. Not too far from Somerville, at St Anne’s College, one can find a portrait of Iris Murdoch. It stands in sharp contrast to the gilded-framed, baroque paintings of Oxonian males in decorated uniforms. Painted by Marie-Louise von Motesiczky, Murdoch sits pensively on a chair in a compact room. The loose, partly impressionistic brush strokes, the muted colours and the undistinguished backdrop: all convey a sense of quiet introspection and even disorderliness.

Catalysed by her visit to Cambridge in 1928, Woolf wrote in A Room of One’s Own: “Lock up your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind.” We find evidence that the city indeed equally belongs to women who, even when access to the University was denied, formed an integral part of its literary legacy: what remains and is passed down to us are scattered traces, often found in the quieter corners of Oxford. They reveal a parallel literary history, one built not for celebration and visibility, but to be experienced in quieter streets, uncelebrated houses, and modest plaques.