Every Magdalen member remembers their first encounter with the Waynflete Building. Sticking out a little obtrusively amidst the serenity of Addison’s Walk and the college’s two grandiose deer parks, the purpose-built, ‘60s-era block is hardly the accommodation most undergraduates had in mind when they received their offer. Especially not from the college that inspired C.S. Lewis’ Narnia.

It was almost certainly the aubergine-purple carpets that dashed my admittedly pretentious vision for a room, both quaint and saturated in dark academia, on that first day of Freshers’ Week. Or perhaps it was the radioactive green wardrobes. The glaringly non-existent sink equally did not help matters.

Still, when I look back on that morning, it is not the disturbing interior design decisions that stand out. Nor is it even the tropical climate that greeted me immediately upon reaching the fourth floor, despite it having been an uncharacteristically chilly October (still a mystery to fellow ‘Riverside’ occupants).

What comes rushing back isn’t my inaugural experience of the ‘Flete’ – as its residents affectionately nickname the Waynflete building – but rather the unmistakable, melodramatic camaraderie that seemed to thrum through its beige walls. Behind the imposing colour of my cupboards, I had relished discovering decades of choicely worded protests and gripes, juxtaposed with innumerable ‘Long Live Waynflete’ avowals and hearts all scrawled into its insides.

It was a tale of two halves: a study of how somewhere ostensibly drab could nurture such a remarkable warmth. A kind of original ‘misery porn,’ if you will, where collective vexations forged meaningful connections.

1st-year Magdalen student and fellow-Waynflete-survivor Abigail Grant captured this very sentiment and more in her Waynflete Building Exhibition, This Room Their Lives.

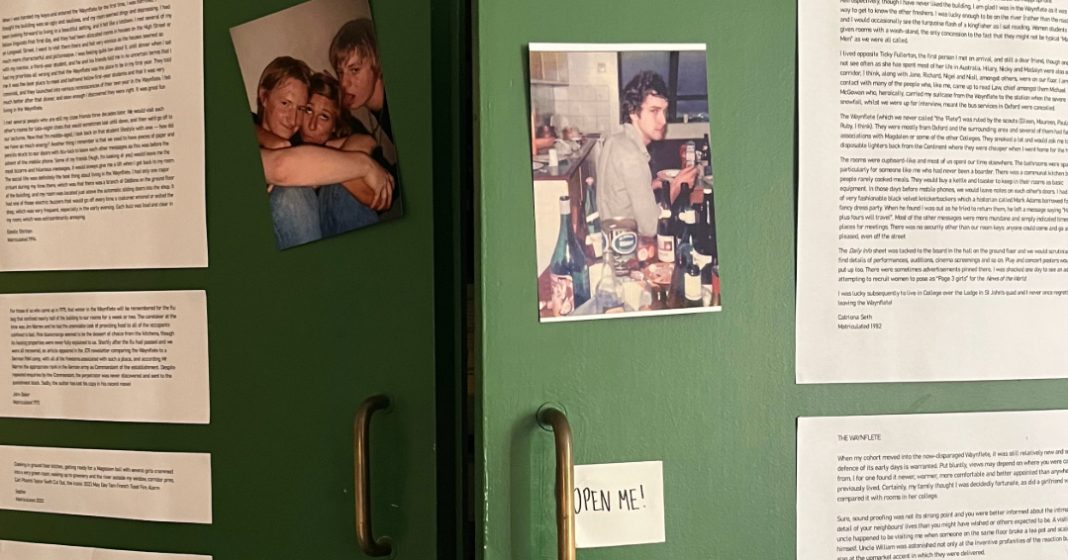

Stepping into room 13 of the Waynflete, where her love letter to the building’s inhabitants is housed, visitors are thrust into a time capsule. Yet, it remains unmistakably the room of a student you may come across now, ageless in its charm and unruliness. With the gentle hum of a Weezer tune in the background, I was immediately charmed by the careful curation of books, photographs, and posters that together told the story of an undergraduate who could have belonged to the class of 1995 or 2025.

The anecdotes Grant has dexterously sourced from dozens of alumni, detailing their experiences’ of living in the Waynflete, are perhaps the most compelling part of her exhibition. There are too many wonderful tales to recount them all, but one in particular stands out. Estelle Shirbon (matric. 1994) recounts how, on first entering the Waynflete, she was left “horrified.” Yet, she found some of her closest friends between the purple floors and green wardrobes.

Grant has crafted an ode to a building that doesn’t necessarily lend itself to poetic recollection. It takes true patience and flair to sift through all the whinging, all the grumbling – and voices like Catriona Seth (matric. 1982), who professes, “I never once regretted leaving the Waynflete!” – to produce something so heartfelt on the other side.

Michael McGowan, matriculating in 1982, wonders what the college’s founder would make of the rise and fall of the building to which he lends his name. “Unlike it,” he remarks, William Waynflete was “the ultimate survivor…having died of old age in his bed despite serving on both sides of the Wars of Roses.” It has to be said, however, that many a middle-class Magdalen Fresher – myself included – have at times treated their sojourn in the ‘Flete’ as akin to a noble sacrifice.

Grant does well to tension this entitled tone against the quiet luxury of living amongst so many of your dearest friends, sharing everything from late-night gossip to a singular kitchen that does not produce inexplicable odours. Indeed, Grant told Cherwell how she “wanted to create this exhibition to honour both the loathing and the love people have for the Flete,” admitting that while “it’s clearly not the most beautiful building…it’s full of memories, and…didn’t want those to be lost when it was demolished.” If her ultimate intention was to show off “the kind of real history,” she says she tends towards, a history centred around “people falling in love, making lifelong friends,” Grant certainly achieved it.

The photos, which deck almost every inch of the room, are deftly selected. They demonstrate that while mohawks and terrible polo shirts might separate more recent Magdalen freshers from older ones, they share a significant, common experience.

The Waynflete is a building that everyone loves to hate, a building that oftentimes seems to pose more challenges than it is worth. Even in death, its imminent absence – more than provoking fond memories – comes with further practical problems for undergraduates. Recently, second – and third-year Magdalen students have protested their accommodation prospects now that freshers will be situated inside college walls, which had previously been their stomping ground.

If the Fletes’ long history is to be boiled down to one anecdote, Grant’s rewarding find of one describing the Great Fire of ’82 is a good fit. The image of 70 first years bellyaching as they stand on the pavement in their pyjamas in the middle of the night – but silently revelling in the comradeship and pandemonium of their situation – is emblematic of the melodrama that ties together the diverse inhabitants of the Waynflete Building’s 60+ year tenure.

Long Live Waynflete, indeed.