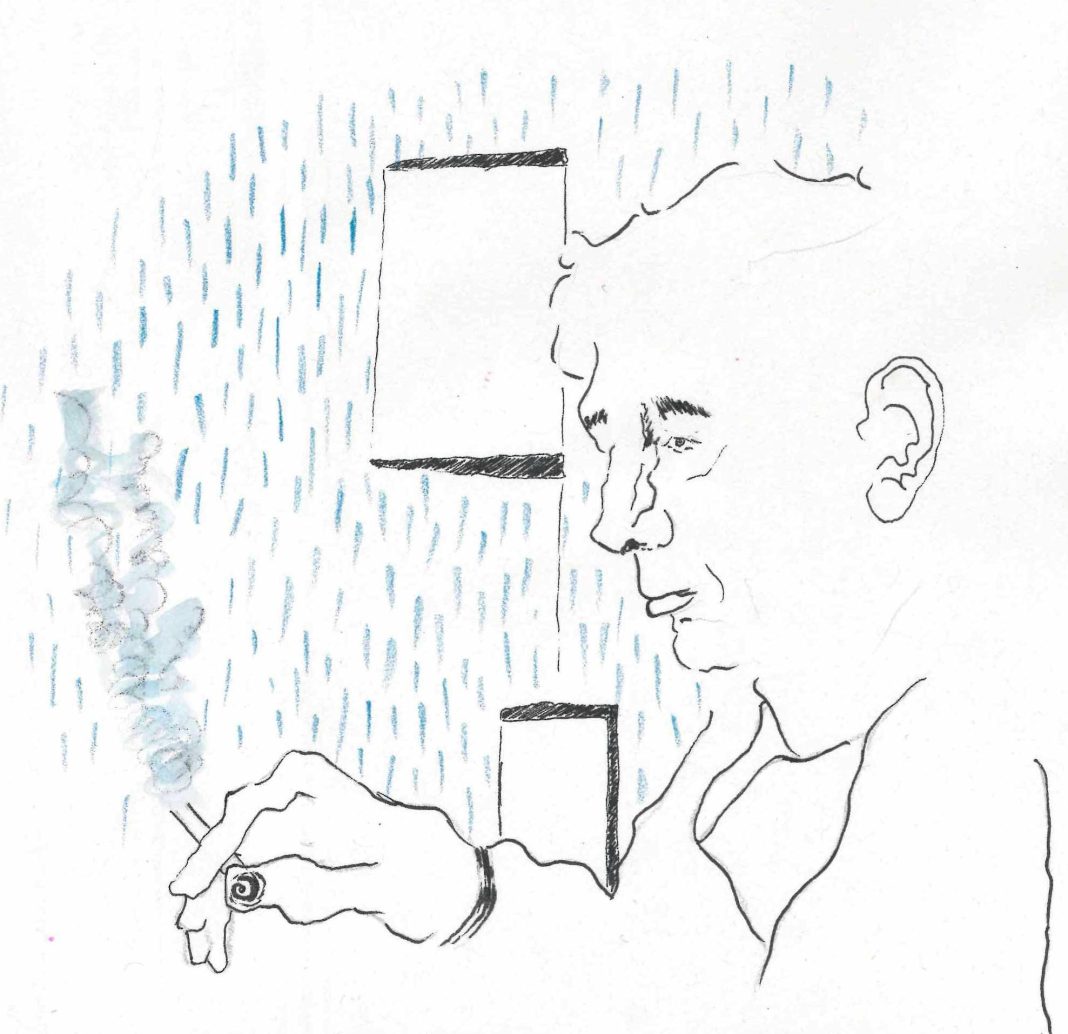

It’s a damp Tuesday afternoon, and W.H. Auden is waiting patiently at the bus stop, umbrella forgotten on the ground beside him. He’s been there seventeen minutes. No one speaks to him, but everyone seems to know who he is, at least they think they do. He doesn’t say a word. The 148 is cancelled again. Still, he stays, unmoving, rain misting his collar, not impatient but vaguely amused. Not quite waiting for Godot, that would be gauche, just the bus that never comes.

The clocks tick on, but time feels adrift. A kind of metaphysical delay hangs in the air. And Auden, tweedy and abstracted, does not resist it. He leans against the bus stop, a man perfectly at home in suspended time, a philosopher of missed connections. Around him, students rush to collections and clutch tattered library books like shields against the wind, whilst tutors dart toward High Table. But Auden waits like the human form of a footnote: tangential, though necessary, and often overlooked.

He would not look out of place in Oxford now. You could imagine him dawdling past the Taylorian, rain soaking his cuffs, pausing outside the Rad Cam to scowl vaguely at the architecture. His shoes would squeak down St Giles as he muttered a half-rhyme about exile. He might even be seen in the Upper Reading Room of the Bodleian, scrawling something illegible on an index card, then promptly losing it forever. His spectacles might fog slightly, but he would not mind.

Oxford is, after all, a city designed for delay. There are buses that never come, travel grants that never arrive, theses that never resolve. The system seems built not to accelerate thought but to gently mulch it in slow, damp bureaucracy. Like Auden’s bus stop, Academia is a space of sustained anticipation. You wait for funding, for feedback, for permission to begin. You wait to be noticed. Or worse, understood.

We tap our bus passes, hoping something will validate us.

And when it doesn’t, when the red light flashes and the doors hiss shut, we retreat to the safety of ritual. Pret filter coffee. A wander around Blackwell’s. A return to the desk where ideas come slowly, if at all. Delay becomes a liturgy of sorts, a form of quiet, ironic worship. Even the pigeons seem to linger on purpose.

This waiting, so ordinary and passive, starts to feel like the condition of thinking itself. Ideas take time. Or at least, they take waiting: waiting for a sentence to click, for a thought to emerge, for a supervisor to reply, ideally without the words “slightly disappointing.” A kind of unspoken purgatory defines academic life: a limbo between potential and irrelevance, between imagined genius and absolute exhaustion.

Slowness becomes deliberate.

Auden, who once wrote that “poetry makes nothing happen,” knew the quiet dignity of non-arrival. He saw waiting not as a weakness but as a witness to modernity’s speed, its desperation, its refusal to pause. He would have loathed our timelines, productivity apps, and endless small performances of usefulness. Instead, he offers an alternative: to stand still and feel something. Or perhaps, to stand still and feel nothing, observing the nothingness for all its worth.

In the rain, the bus stop timetable flickers again. Still no bus. A fresher mutters something about walking to Jericho. A don in an oversized scarf sighs audibly. But Auden is unbothered. He has his coat, mind, and, presumably, a few lines of verse he’s been carrying for days.

He is not waiting for transport. He is waiting for meaning.

And perhaps we all are, in our strange little offices with flickering radiators, our Moleskines full of crossed-out ideas, our unread JSTOR tabs, waiting to write, to be read, to matter, or waiting for the courage to be still.

Let the 148 never come, let the timetable remain in flux, and let the rain fall endlessly onto the cobblestones.

For now, Auden is here. So are we. And that feels like a kind of arrival—tentative, quiet, and entirely our own.