On the 16th May, the man who stabbed author Salman Rushdie following a literary event in 2022 was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Almost three years after the assassination attempt on Salman Rushdie, it feels there are two predominant approaches to reading The Satanic Verses: getting lost in its immense creative energy, or keeping at a remove, with its political implications in mind.

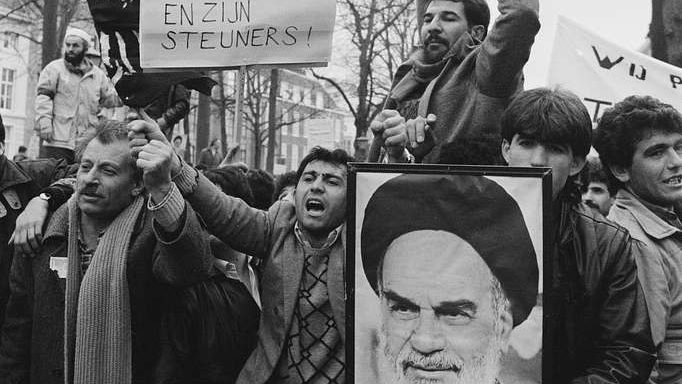

The response to Rushdie’s novel has been nothing short of extraordinary. On the one hand, it won the Whitbread Novel Award and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1988. On the other, Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa (a ruling by an Islamic authority) against the author, following bans in seven countries in 1989. In Rushdie’s case, this was an order for execution against a bounty of $3 million. And as already alluded to, Rushdie was eventually attacked (and ultimately lost his right eye) during a talk at the Chautauqua Institution.

Alongside works such as Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and Beloved, The Satanic Verses is a cornerstone example in knotty issues like the banning of books, freedom of expression, and postcolonial theory. However, Rushdie’s novel goes beyond the boundaries we are used to: the author (or his novel – it is difficult to pin down) became indirectly embedded in British-Irani diplomacy for ten consecutive years following the 1989 fatwa. A consideration of this political background reveals the interpretive grey areas that fictive literature inhabits.

The Satanic Verses details the paths of actor Gibreel Farishta and voice-actor Saladdin Chamcha from India all the way to Britain. This journey, however, is anything but smooth: their flight, Bostan 420, gets hijacked and blown up above the English Channel. The two, however, do not fall to their death – they are instead rebirthed. Gibreel’s nights become riddled with dreams of Jahilia, an imaginary realm in an unspecified desert, where he becomes Allah’s Messenger to prophet Mahound. Simultaneously, Saladdin metamorphoses into a goat while his English wife has an affair with someone new.

The title is a reference to Qur’anic passages in which Muhammad appears to venerate three pagan goddesses, which sits uneasily with Islamic monotheism, and so has, controversially, been represented by scholars in the past as the product of Satanic suggestion. This title, along with the Jahilian passages (where allusions to Satanic suggestion are played out), were the main elements triggering the fatwa.

Despite the sheer wonder of the novel, it is difficult to ignore its political and religious voice. Its dazzling passages also serve as areas of contestation about the roles of the author, of governments, and of religious authorities. Lots of commentators, like Brend Kaussler in his piece ‘British-Iranian Relations, “The Satanic Verses” and the Fatwa: A Case of Two-Level Game Diplomacy’, have discussed the political potential of fictional works. In approaching these connections, however, we must ask ourselves: how far should literature be allowed to infiltrate and influence global politics?

A core conflict surrounding The Satanic Verses lay between religious orthodoxy (the Irani perspective) and freedom of speech as a human right (the British perspective). This is not to reinforce a binary of the West and the Middle East: especially in the late eighties, when a mere handful of people (mainly men) were making decisions over the novel, it is self-explanatory that they were and are not representative of their respective nations.

Immediate responses to the fatwa included keeping Rushdie under police protection, delaying the establishment of the British Embassy in Tehran, the official breakdown of Iranian-British relations in March 1989, and eventually the taking of hostages in Lebanon and Tehran. Though neither the hostage crisis, nor its resolution, are closely related to the text itself, the book worsened the hostility between the negotiating parties, hindering the initial bilateral efforts to establish and sustain British-Iranian relations. In this context, Penguin Books did not go ahead with the publication of The Satanic Verses paperback – a clear sign that literature could and had taken on political resonance. We may view the publication, then the fatwa, the mistrust, the conflicts, and the conspiracies as a sequence of domino effects––but where does it end? Was this politicisation Rushdie’s intention?

We must return to the book itself. The plot is interspersed with sinister magical realism; Jahilia is fragmented by religious conflict that Gibreel cannot resolve and neither can he navigate his relationship with Alleluja Cone or the bustling capital of England. Saladdin experiences the physical manifestation of hyperbolic racial stereotypes in his metamorphosis and struggles to resolve the tension with his Indian roots and aspirations in London.

Preceding the first two pages of the novel (famously the only bit of the novel actually read by Rushdie’s assailant), we are faced with a title that immediately centres the incident of the Satanic Verses. And Rushdie alludes to it again in a scene in which he weaves Mahound (a prophet), Gibreel (the protagonist and God’s Messenger), and the narrator together as they wrestle. The resulting confusion prompts Mahound’s belief that “it was the devil’’ who dictated his last message to his community, in which he expanded their religion to polytheism. In light of the title, the narrator’s voice seems to match up with Satan, and Mahound with Muhammad. The implication is one that deeply disturbed Islamic orthodoxy.

Straightforward allusion is however uncharacteristic of Rushdie. The whole “Mahound” section interrogates authority, translation, poetic and political expression, and obfuscates the narratorial persona. The “I” of the passage is elusive, intrusive, cynical – at several points it does not match up with the Satan-figure of the Qu’ran. Instead, Rushdie seems to be questioning the validity of an omniscient interpreter, narrator and distributor when it comes to story-telling. It is unclear from recontextualisation, then, whether the conclusion drawn by Ayatollah Khomeini was indeed Rushdie’s message; here literary criticism assumes political ramification.

The Satanic Verses layers its theological discourse with a magical realist depiction of diasporic experiences in the UK, quite separate from theology. For instance, one of the protagonists, Saladdin Chamcha, metamorphoses into a goat shortly after touching the shores of England, and is detained by police for illegal immigration. In captivity, Saladdin’s conversation with a fellow prisoner discusses mechanisms by which the white supremacist British depictions misconstrue immigrant and diasporic identities.

Rushdie’s hybrid narrative of religion, migration, and the struggles of cultural assimilation involves more than theological debates on unorthodoxy. Nevertheless, diplomatic tensions strongly centred around the latter, masking, unfortunately, the psychological aspect and cultural critique. Some responses to the novel destabilise the text to an extent where it becomes barely recognisable. The layered narrative investigates several aspects of the human condition, aside from the Jahilian reimagination of the Satanic verses incident in the Qu’ran, and it is in those moments that his craft shines through, where readers lament that his creativity was (and sometimes still is) overshadowed by diplomacy, the Defence Committee and book bans in several countries.

The Satanic Verses may challenge aspects of religion, but this is by no means reserved for Islam alone, and the diplomatic responses have blown textual implication out of proportion. However, with this novel, as with many, it difficult to just stop analysis and interpretation. Fiction is ultimately inextricable from the political context in which it is conceived and interpreted. Perhaps that is why tensions around the book have never ended; neither will the conversations, after all.

by Ivett Berenyi