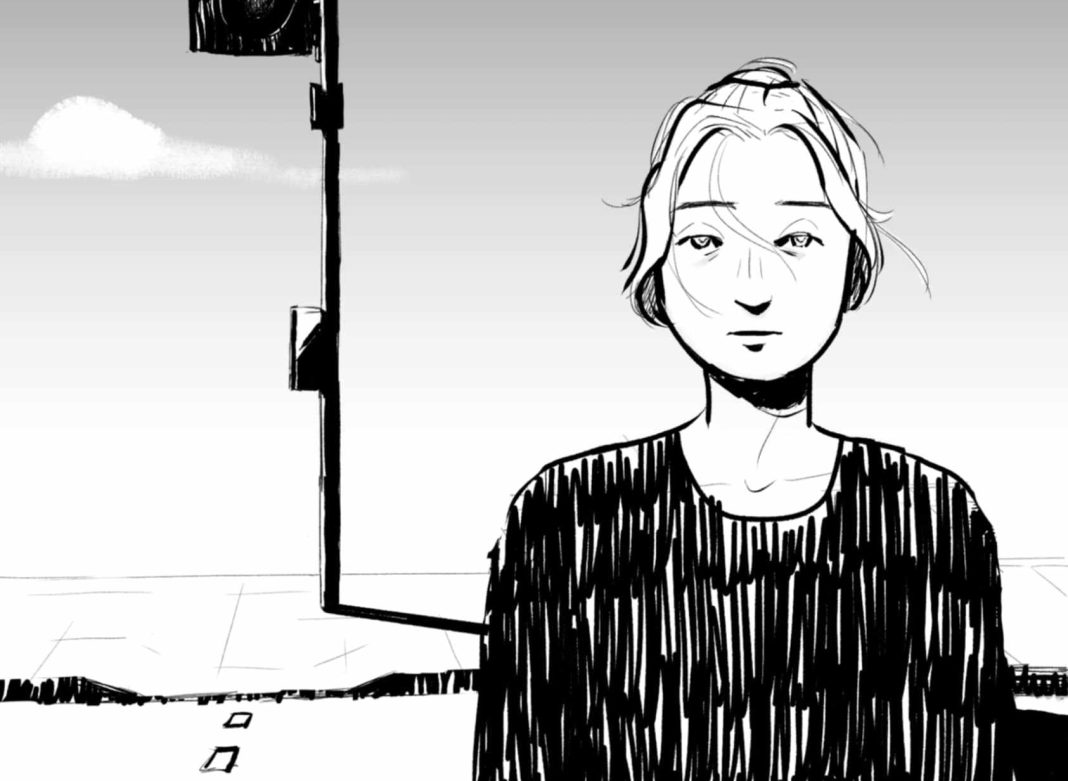

I jolt from dreams of silence into a wakefulness of traffic. The school rush, honking and shrieking like geese outside. I forget that other people’s days start before noon – the leisurely life of university – but today I join them. Wash my face in the sink, dress in black. My roots have grown out these past months. Of all the days to notice, it has to be today.

I sit on the edge of my bed to catch my breath.

I can’t stop for long – the train station is thirty minutes away and to tempt fate would be unwise at best, devastating at worst.

Purse, phone charger, paper tickets (what a novelty!), and keys. Enter the throng and the bustle of real life. Little year sevens flocking towards the open doors of the schools, cowering under backpacks which would put Mohammad’s mountain to shame. They glance in panic and shame at the time, run with all their might to be ten minutes earlier to register. Their parents watch from a safe distance, engines on as if to disguise the fact that they will sit there, intently focused, for at least another ten minutes. I do not have the luxury to linger and watch both the past and future unfold. I don’t remember being that small, that blissfully unaware, but like a bullet in the leg the truth of it embeds and will not unlodge. The passage of time is a bloodthirsty hound.

On the train I play choral covers of Radiohead songs and think about the looming deadlines which have characterised my term; the fact that I haven’t received a text back from the PPE-ist at St John’s I’ve been seeing; how one less person now remembers me as young and careless and shockingly blonde.

Tears clog in my sinuses – I feel them everywhere but my eyes. Somewhere just off the mark, just out of reach. I wish I’d brought water. I read years ago you can’t cry and drink simultaneously, and though it’s yet to work, it gives my mouth something to do other than tremble. Wish I’d brought food. When does one eat on days like these? My friend told me wakes often have food, but what does she know?

No one she knows has ever died.

Change at Paddington. Tube is packed.

I always thought London was this great car-less city, with everyone crammed into metal tubes, on their way to mindlessly turn cogs in some behemoth machine I could neither see nor understand. To have a car would be too personal, too rebellious, too close to straying from the written path. Yet, in my grandmother’s house, with its creaking floorboards and Turkish rugs, there was always the constant chatter of cars. I would lie awake watching the room shoot in and out of shocking blackness as the headlights outside came and went – ships skirting past my harbor.

I, having grown up somewhere between nothing and nowhere, found this of course to be terribly distracting. I would always fall asleep on the sofa the next day mid-way through breakfast, when the murmur of TV and conversation masked the unfamiliar buzz of city life.

But inside a car the world was different, taking on new shapes and meanings like clay in my hands.

She used to drive us places, my sister and I. Before the migraines started, she would drive two and a half hours to come and visit us. Take us on walks around our favourite parks. Kiss our kittens and let us regale her with our dolls and dinosaurs.

Or, if we were in London, she would bundle us into that beaten sedan with no headrests on the back seat, and take us to the cinema, or the Tower, or the Eye. There must be a picture of us three in every corner of the city. I can still taste salted caramel ice cream, feel the sun on my face, her hand in mine.

So it goes.

I mustn’t dwell. Wouldn’t want to miss my stop. A train whizzes past on the other track. I used to think they would run all night, perpetually roaming the tracks like creatures with individual minds and powers. Foxes howling in the woods outside my bedroom; the pitter patter of cat claws in the hallway at 3am. These sounds spilling into my dreams like milk, lullabies of the country.

I cannot, even now, imagine life stilled. The bluest ribbons of blood fading grey. The babbling pulse damned. Wet paper bags in the chest; whatever happened to breath?

The speaker crackles, Enfield Chase. Disembark.

Meet my mother on the platform – fall into her embrace like my strings have been cut. Walk the familiar paths, past the cracked painted fence and crossing car-heavy streets. I cannot quite accept it may well be the last time I will do this. I want to stand on the precipice of youth and lean backwards, splashing through the warm waters of summers, lost until I emerge, unscathed, in a spring when nothing bad has ever happened.

Life goes so very quickly. I shore against my ruins faded pictures and pink-princess birthday cards, but still it passes unhindered, unwavering. Motorway traffic versus some poor squirrel, caught up in hamartia, or animal instinct.

Who am I to halt time? Who am I not to try?

I gnaw on the bones of time to no avail. Hard and fast, it whispers unrelenting, unforgiving in my ears. A cacophony of loss I can only fathom by tracing the edges.

As we walk down Green Dragon Lane, I think for the hundredth time it could do with a pelican crossing.

Of course, it makes it easier for the hearse that it doesn’t. My parents, sister, uncle, and a woman who introduces herself as Martynne squash into the cars that will follow. I’m sure she tells us more, but I cannot bring myself to listen. Let others smile and socialise – I breathe in the dust and the life which lingers, despite the absence I cannot ignore.

Say goodbye. Buckle my seatbelt. Not that I’d need it – someone is walking in front of the hearse, top hat and morning coat on. I thought this kind of ceremony was reserved for other people.

It seems, even now, as though it cannot be happening to me, despite all evidence to the contrary.

During the service, I tell myself that this is happening to somebody else. That I am not here, watching my grandmother’s life in pictures, my sister crying and holding my hand. I read the words in front of me – a book of hymns. Do people usually sing?

The person this is happening to, who is not myself, but some far removed girl who can mourn, swallows grief whole. I – she chokes on memories.

Nails dig into palms, teeth clench. We stand at the coffin, backs bent like apostrophes, and I do not know how to speak to a body, cold and silent; hidden away and removed from everything bright and dazzling and new. We turn away. I follow my sister into sunlight – an Orpheus without hope – and wonder if there is a heaven, if the seasons are different to earth.

After the wake, I am put on the opposite train to the rest of my family. They wave to me as my train leaves the station, and I begin my odyssey to the city of spires. I read Little Women. Stop before Beth dies. Google ‘books where nothing bad happens’ and am forced to accept that to live is to grieve. Call my friend from the third train so she can meet me at the station. We pick up dinner and she asks if there was food at the wake. I tell her there were sandwiches and drinks.

We eat cross-legged on the floor. If I wear these clothes tomorrow, I will have sat a miniature shiva. No time for a full-one, there are meetings to go to, and deadlines delay themselves for no man.

I go to bed early. Engines croon and hum outside my window, fending off sleep.

I am twelve years old, my sister snores next to me, at the top of that rickety house I once knew like the back of my hand.

Everyone is alive.