Many schools across the country dream of sending just one student to Oxford. For some, though, it’s an expectation.

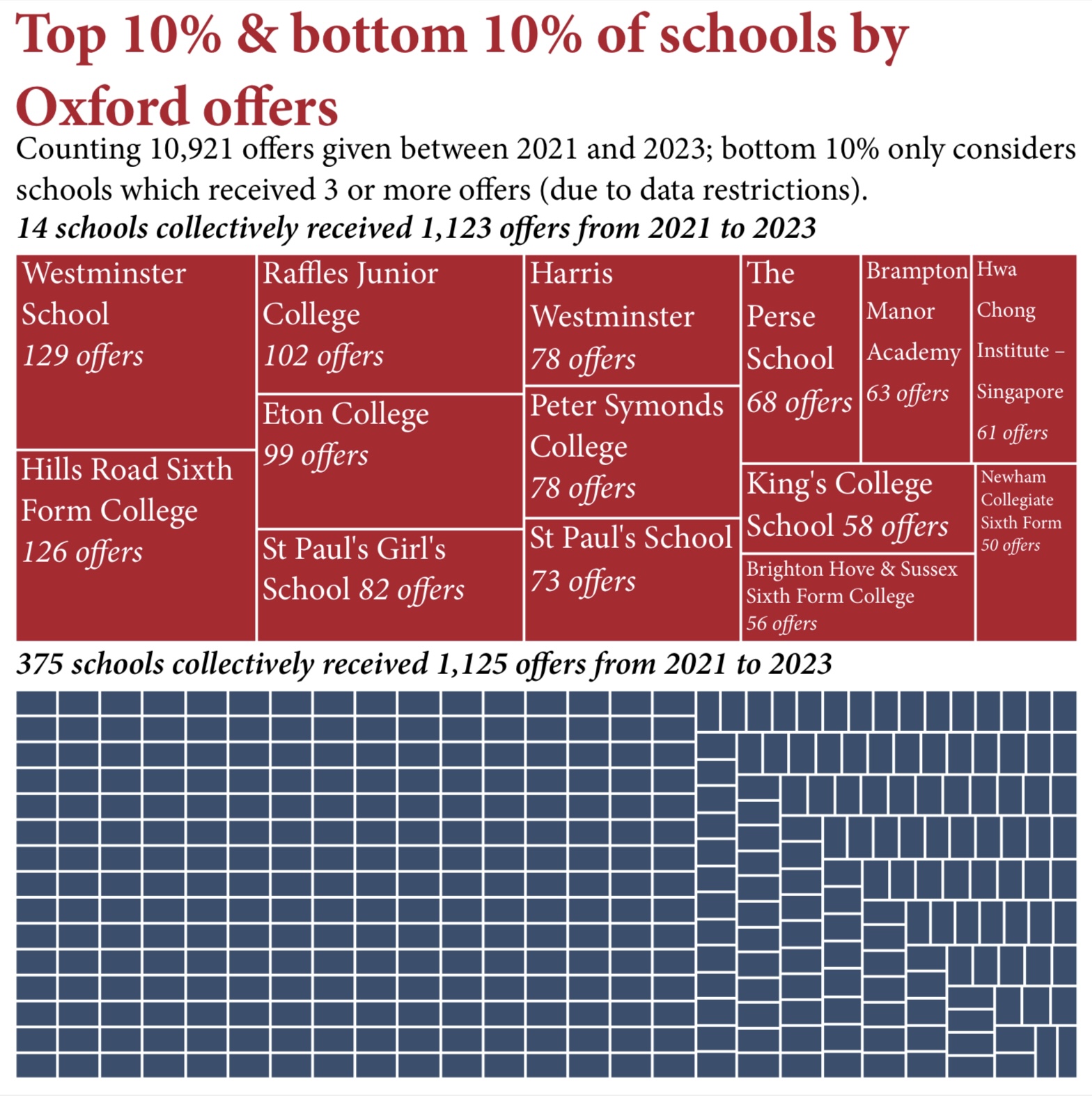

The image of Oxford as a training ground for the elite has somewhat withered, and the stereotype of the likes of Eton and Harrow as feeder schools is arguably less persistent. This can, in part, be put down to the drive for equality of opportunity, recruiting the most promising students from a range of backgrounds. If this is true, however, why is it that of the 3,721 offers given out by the University of Oxford last year, over 10% came from just 14 schools?

The 14 schools that make up over a tenth of Oxford’s offers are comprised of eight private schools, with the likes of Eton College and Westminster School, of course, placing highly. Cherwell’s analysis of data from recent Oxford admissions cycles reveals an unsettling trend, where a few powerful institutions have a chokehold over the entire recruitment process.

The top schools

Westminster School topped the list of schools with the most offers, an infamous fee-paying institution that has educated the likes of Louis Theroux, Nick Clegg, and Helena Bonham Carter, to name a few. Westminster received 38 offers last year, having submitted over 100 Oxford applications – its offer rate sits at 37%.

An alumnus of Westminster School, currently studying at Oxford, explained to Cherwell that “there is definitely a widespread feeling that Oxbridge is the goal. If you’re sitting in a classroom, either you, the person to your left, or the person to your right is likely to get in, statistically”.

The student told Cherwell that the admissions process for Westminster School itself is somewhat geared towards Oxbridge admissions in the first instance. Prospective sixth-form students sit a TSA, the same style of admissions assessment that Oxford uses for many of its courses, like PPE and Economics and Management. When it comes to university admissions at Westminster, students are supported by regular sessions alongside others applying to the same course, interview practice, and general preparatory aid.

Another one of the schools with the most offers was Harris Westminster, a state school situated just down the road from the aforementioned Westminster School. The school was founded in 2014 with the aim of achieving the same Oxbridge rates as its neighbour, which has supported Harris Westminster for the past decade. It is highly selective and students are chosen through a rigorous interview process.

The school had an impressive 32 offers, which amounts to more than the more traditionally prestigious Harrow, Rugby, Charterhouse, and Sevenoaks combined. One Harris Westminster alumnus who is currently studying at Oxford told Cherwell that “from my experience, the support was extensive but also quite high pressure. Unlike regular sixth forms, it was mandatory and scheduled into our weekly timetables for us to partake in societies as well as ‘cultural perspectives’ – two extra classes on a specific academic

topic, such as feminist philosophy.

“As much as it was a privilege to partake in these, our days were already roughly 8:30-5 including (a half day of) saturday school in Year 13. A lot of teachers really pushed coming off as ‘well-rounded’ for our personal statements, but the timetables that we were on meant most people

were generally exhausted and burnt out.

“There was certainly also a cultural dimension of the preparation for Oxford – our terms also had silly names, we grew accustomed to weekly assemblies in Westminister cathedral, and were held to a certain level of professionalism that I haven’t understood to be the case from any friends attending other sixth forms.

“The culture around Oxbridge was uniquely cut-throat at Harris – it wasn’t just that we all went to a selective school, but that many of us were low-income, first-gen, or

generally from underprivileged backgrounds – we had the academic expectation of a private school but very often

without the safety net of a well-off or suportive family.”

Another Harris Westminster alumnus, currently in their first-year at Oxford, told Cherwell that during the admissions process, “a lot of resources are available. Mentors are assigned, and you have talks about applying.” However, the student did not believe that there was pressure to apply to Oxbridge, and their form tutor even said that “Oxbridge was not the be-all and end-all.”

Harris Westminster benefits strongly from its relationship with its pricier neighbour – the former sends students to take A-Levels in the latter, in subjects that it cannot offer due to having less resources. Even on their website, Harris Westminster’s Executive Principal, Gary Savage, describes Westminster School as “the solid ground [they’re] built on”, and states that without their support, Harris Westminster would be “less scholarly [and] less confident”. Where, then, does that leave the thousands of other sixth forms that don’t have equal resources?

The inequalities

Of the 14 schools that constitute over 10% of offers, all but two are in the south of England. In fact, the school situated farthest north is King Edward VI School in Stratford-upon-Avon, just south of Birmingham, and the only other non-southern school is in Singapore. Six of the fourteen schools are in London – this can be, in part, blamed on population density, but the concentration of such powerful educational institutions in and around the capital points to a deeper problem – the disproportionate allocation of elite educational resources to the affluent south.

Oxford’s feeder schools are not inherently private, but rather, they are overwhelmingly southern, selective, and embedded in networks of privilege. This results in a de facto regional divide, where promising students from the north, regardless of talent, face a tougher climb to higher education. Oxford’s access efforts may be well-intentioned, but they continue to overlook structural disadvantages facing entire regions of the country.

Cherwell found that parts of the north of England were underrepresented in applications to the University, with applications from Yorkshire and the Humber making up only 5% of applications and 8% of the overall population. Moreover, Cherwell revealed that colleges’ outreach programmes did not reflect the regional underrepresentation in applications, with more colleges being linked to London and the South East than any other region, despite these regions’ overrepresentation in the statistics.

These inequalities have only deepened in recent years, and after 14 years of Conservative government, 70% of schools in England in 2024 had less funding in real terms than in 2010. Given its reputation for elitism and historical ties with the establishment, it is no surprise that Oxford comes under scrutiny for its access and outreach efforts given it lags behind the national average number of state educated students by over 20%. In fact, in 2021, it had the seventh lowest proportion of state educated students in the Russell Group. Within these abstract percentages, there lies an even more pressing issue that is difficult to solve – how Oxford guarantees diversity within the state sector itself.

The University has implemented outreach programmes like the UNIQ programme and Opportunity Oxford in the last two decades, and each college has their own outreach programmes in order to combat these issues. However, Cherwell found through Freedom of Information requests that despite individual colleges increasing their outreach to state schools, applications from state schools have barely increased, and admissions from state schools have stayed the same.

Education and the government

Secondary education in Britain received sustained investment under New Labour, whose top priority was ‘education, education, education’. When Blair came to power, schools were renovated for the first time in a quarter of a century, class sizes shrunk, and money spent per pupil doubled from 1997 to 2008. Blair had a vision – he wanted to transform all state schools to the point that even those affluent enough to send their children to private school would choose not to.

Blair took inspiration from a Swedish model of education, where schools are largely autonomous units that compete to be the best. A large proportion of the Labour party was still wedded to uniformity, and the word ‘choice’ shook the core of the party. The likes of John Prescott, Deputy Prime Minister until 2007, feared that the Blairite vision of academies would make them into grammar schools with a different badge, as the label of ‘good school’ is strong enough that middle-class competition becomes rife.

The left of the Labour Party were therefore wary of creating a ‘two-tier’ schooling system by introducing academies, though a multi-tiered system did already exist given the influence of faith, postcode, and region within the state sector itself.

One key figure in shaping New Labour’s education policy was David Blunkett, who served as Blair’s inaugural Secretary of State for Education and Employment until the next general election, when he was promoted to Home Secretary. Blunkett told Cherwell that when he was put in charge of education over 25 years ago, one of his missions was to “challenge the very narrow access to colleges at Oxford and Cambridge from across the UK”.

Blunkett explained to Cherwell that instead of providing funding to individual colleges, it was decided that the central University should be responsible for overall finance and developing access policies. Since then, all universities have been asked to develop such programmes, overseen by the Office for Students, which was set up under the Conservative government back in 2018. However, Blunkett lamented that “sadly, things have not worked out as intended!”

He told Cherwell that “gestures have certainly been made in the direction of engaging with very specific schools, ticking the box of ethnicity or deprivation, or both. In other words, to be able to say, that the University, and specifically individual colleges, have reached out to recruit students from sixth forms or sixth form colleges in the state sector, and to display just how well they’re doing.”

However, for Blunkett, these attempts to widen access have merely been a facade, improving the chances of just small numbers of young people. “Unfortunately, this is all smoke and mirrors. Whilst some young people have benefitted – almost wholly from the south of England – the same old procedures continue to favour a slightly wider group of private schools than was true of the past, and a modest improvement in access from those educated in state funded secondary schools.

“But the overarching message remains the same. If your family has a historic connection with the University, if the school has built up a direct link with the University, and if you live south of Birmingham, then your chances of getting a place will be substantially greater than an equally bright young person from a different background living somewhere else.

“It is not that admissions tutors don’t care, nor that the University haven’t tried. It’s just that it’s built into the DNA. If you think you’re doing the right thing, you can justify, in your head, just about anything. That is, of course, if psychologically, as someone employed at the University, you’ve made the necessary adjustments to affirm your own pathway to success, and the position you now hold.”

Next steps

The Student Union (SU) told Cherwell that these admissions statistics demonstrate the inequalities across the UK “that Oxford has not only been shaped by, but has historically upheld. While the University has made some strides in advancing access, the disproportionate number of offers going to a handful of highly resourced schools shows how far we still must go in dismantling systemic inequality”.

The SU also highlighted that “it is crucial that Oxford continues to publish more granular admissions data, especially to distinguish between different types of state school. Transparency is fundamental to accountability and reform, and is something that we should encourage across the sector.”

An Oxford University spokesperson told Cherwell: “Oxford is committed to ensuring that our undergraduate student body reflects the diversity of the UK and that we continue to attract students with the highest academic potential, from all backgrounds. We know that factors such as socio-economic disadvantage and school performance can make it difficult for some students to access their full potential before applying to university and therefore use a range of contextual information to help us to better understand students’ achievements.

“Oxford also offers one of the most generous financial support packages available for UK students, and around 1 in 4 UK undergraduates at the University currently receives an annual, non-repayable bursary of up to £6,090. In 2023, 511 UK offer-holders participated in Opportunity Oxford and OppOx Digital, our academic bridging programme developed to support students from under-represented backgrounds in their transition from school or college to our university.

“We continue to build on and expand our access and outreach activities in support of equality of opportunity for all talented students, and last year launched new initiatives in regions of the UK where fewer students currently go on to Oxford. We have also published a new Access and Participation Plan, approved by the Office for Students, which provides a renewed focus in attracting and supporting students currently under-represented.”

For many schools, an Oxford offer still remains a distant hope. The University can preach meritocracy, but as long as its doors are open only for a handful of privileged schools and remain shut to most others, that meritocracy remains a major work in progress.