“The costume smells like vinegar. I don’t know why; it just does.”

Matted, white fur is draped across my upturned arms. I take an experimental, cursory whiff: vinegar, body odor, stale caffeine, and a hint of mint. Easter Bunny, my ass—this is a medieval torture chamber.

“And, don’t ask for a spray. It is a tried and untrue method. You’re just gonna have to deal with it.”

My new boss gives an unapologetic, “sucks-to-be-you-but-what-can-I-do” shrug. He adjusts his name-tag—a metallic clip-on with engraved “Benjamin (Ben) Moore, Public Relations Manager” —with all the double-edged arrogance-insecurity of a workaholic. Wasn’t an “empathic disposition” a prerequisite for this job?

“The school arrives at noon, with the scavenger hunt beginning at one, so the morning will be slow. But, don’t expect to be sitting around doing nothing. The moment the costume goes on, you’re on, understand?”

I give a firm nod, satisfying Ben who proceeds to explain the scavenger hunt event in more detail and the associated duties and ethics of donning The Easter Bunny Suit.

In the life of a broke and aimless recent college graduate (in English, no less), the Easter Bunny life didn’t choose me; I chose it. Living with my parents, with no prospects or lofty goals, and equipped with the lexicon of someone who has read a bit too much Victorian literature, it is safe to say that I needed to fill all this free-time somehow. And, as my father insisted, I might as well earn some cash before actually making money.

So, an opening at Riverside Playland—a small and local amusement park at the edge of town—for costume characters was perfect.

After we leave the office, Ben stations me next to the bumper cars and reiterates my responsibilities, with a dash of public-relations wisdom. I am instructed to stay energetic (“you’re the goddamn Easter Bunny; I wanna see some spring in your step”), stay alert (“kids are ruthless and will grab your tail”), and stay professional (“five minutes: wave, hug, picture, egg, next”). In the case of an emergency, I should let my handler Carla, a freckled and muscled middle-aged woman whose sharp and smile-less face reads more bodyguard, take the lead.

Ben ends his spiel with a stern “Don’t lose the basket” before hurrying off to the Easter Chick manning the log-flume entrance.

Now unsupervised, I am tempted to engage Carla in some polite conversation, but she quickly averts her gaze in a clearly “not-interested” way, so I mollify myself with the very astute observation that rabbits do not talk, anyways.

Thus begins my 10-hour shift: in silence. Since the crowd of scavenger-hunting children will not arrive until the afternoon, I spend the morning bored and jittery. I trace the cracks in pavement until they are too blurry to follow; I count the number of times the coaster crests; I watch, from my periphery, the bumper cars spin and collide. Every now and then, a kid visiting with a parent or grandparent comes up for a picture, as do a couple of giggling teenagers. I play the enthusiastic Easter Bunny as best I can, which consists of exaggerated waves and hops, a predilection for hugging, and a repertoire of poses (hands up, hands down, hands on the hips, hands chest-height and flicked down). Carla monitors the situation, interceding only when one six-year-old is determined to scale my back and yank my ears.

By the time 1pm rolls around, I feel comfortable, if not confident, in my suit and skills. The smell, once overpowering and nauseating, has faded into the background, nearly negligible, and I had managed to draw a smile—well, a twitch of the lips—from Carla. So far, smooth sailing.

When Ben returns to remind us that the scavenger hunt will begin shortly, I am prepared for a slight increase in attendance. What I am not prepared for is chaos. Who would’ve thought that a Wednesday afternoon—the Wednesday after Easter, no less—at some local, low-cost amusement park would draw such crowds. Hordes of children, all sporting St. Vincent’s Prep uniforms, swarm me; they grab at my tail, shove snot-covered fingers into my egg basket, and wrestle each other to get the closest to the Easter Bunny.

However, we manage to survive the next couple of hours, and it is as the crowd thins, the clouds becoming overcast, that an unassuming girl (pig-tail braids, freshly ironed skirt, and soft smile) walks up to Carla and promptly vomits on her. Without a word, she rushes to the bathroom, and I am, for the first time, alone.

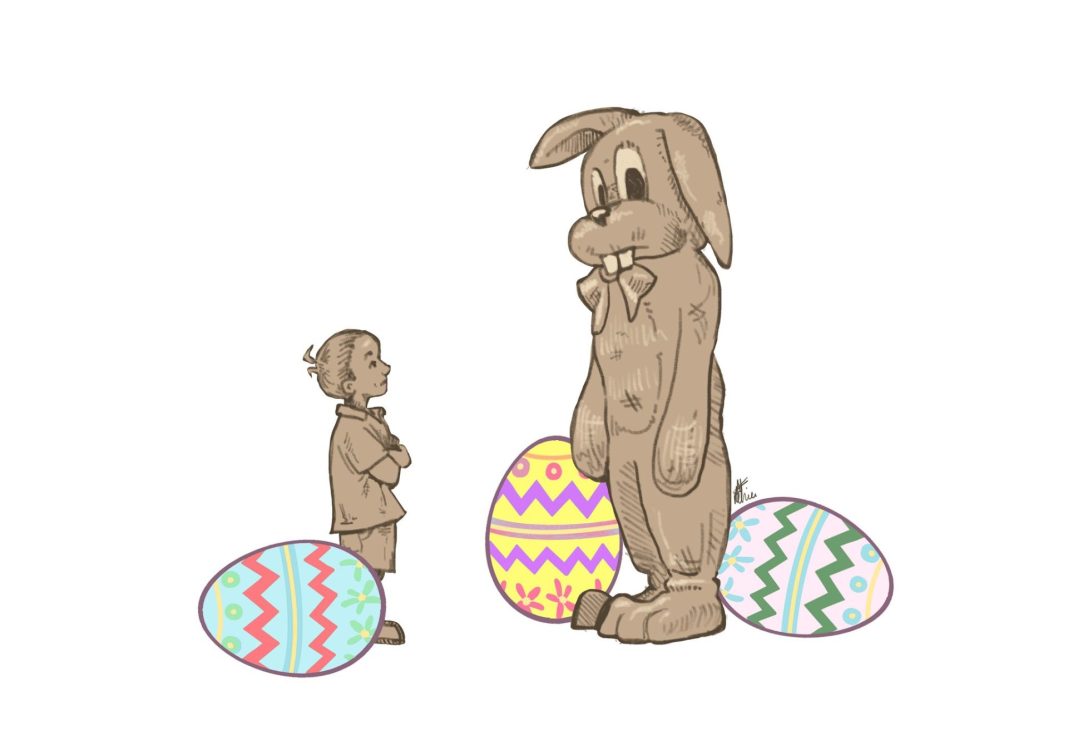

“I know you’re not real.”

It comes from behind, a boy no more than seven with rosy cheeks, fiery orange hair, and glasses perched crookedly on his nose. Like his classmates, he wears a blue St. Vincent’s Prep shirt and beige cargo pants. He stands cross-armed and glaring, forehead pinched and chapped lips ready to castigate any pretensions I might have had to be the real Easter Bunny.

I am in a predicament. Such cynicism demands retort, which I would have readily delivered if not for the fact that I, as Bunny, must remain silent. He waits for an answer, and I resort to shrugging my shoulders and covering my mouth in mock confusion and shock.

He is unmoved, repeating, “I know you’re not real,” and adding, “So, you’re lying, and it’s a sin to lie.”

Slightly panicked, I look around for Carla and, hell, Ben, but the park is desolate save for a few families and a group of high schoolers smoking by the Snack Shack. And, the boy must have detached himself from the rest of the school because I spy neither staff nor students in the vicinity. I rack my brain for some public-relations protocol for dealing with juvenile contrarians but turn up empty. Screw it—time to ad lib.

I squat down, leveling myself with the boy and put on a sweet, airy voice. “Now, why do you say I’m not real? I’m right in front of you!”

That must have been the wrong thing to say, because his jaw clenches and then starts to wobble, bravado turning into petulance. “You’re not real, and I know it!” His eyes go glassy, and he sniffles, “You never came to my house.”

At the sight of tears, I am momentarily paralyzed. This is probably a good time to get help, but Carla and Ben are still MIA and now the boy has started kicking my shin. He whines successive “You never came,” and I am forced to gently grab his shoulders and put some distance between us. His rosy cheeks have gone red with the exertion; he has fogged up his glasses.

My first instinct is to apologize, which I do. “I’m really sorry I missed your house. Even the Easter Bunny can make mistakes.” Then, to start some non-violent conversation: “What’s your name?”

Some of the angry energy has dissipated, and I feel his body deflate in my arms. “Eric,” he croaks, before continuing, albeit softer and more somber, “There were no eggs.”

My throat tightens. “Well, Eric, I apologize for missing your house this weekend.” I grab my basket I had placed on the ground. I dial my enthusiasm up. “But, see here, I have some eggs now for you! They’re for you—please take some!”

There are distant, muted screams as the coaster crests; another round of chattering people enter the bumper car track. Eric gingerly grabs two eggs, one red and one blue, in each hand. He traces the plastic, the ridge that divides each egg into two halves. “Red is my favorite color,” he says.

I lightly tap the other egg. “And, blue is my favorite.”

That makes him smile. “So is mommy’s.” He then shakes the egg, jelly bean rattling from within. I encourage him to crack the egg open, to have some candy, but Eric resolutely refuses, protectively bringing both eggs closer to his chest.

Something troubles him still. In a soft voice, a near whisper, he outlines a rudimentary logic: “No eggs means no Easter Bunny. No Easter Bunny means it’s not real.” But, of course, I pose a problem, and he looks at me and wonders, “Who are you?”

He continues to stare, as if piercing through the matted, white fur and vinegar stench, as if searching for an answer. I see his mind whirling: the divot between his brows; his pursed lips; his scrunched-up nose. Then, he states: “I haven’t seen Mommy in a while.”

I am, strangely, at this moment reminded of high school English—figurative language, the power of metaphor, meaning and meaning-making inscribed on our very tongue—and I almost blurt out a butchered, Faulknerian “Your mom is the Easter Bunny,” when footsteps sound behind us, and I whirl to see a young women rushing over. Carla speed-walks behind her, shirt wet with sink water.

The young woman—a sticker name-tag reads “Ms. Walker” —crouches down next to Eric. He shyly turns into her arms as Ms. Walker softly chides (“You can’t go running off like that”) and soothes (“Everything’s going to be okay”). She grabs his hand and whispers a quick “Sorry about that” and “It’s been a tough time for him” before walking back to join the group of St. Vincent’s Prep children watching wide-eyed.

Carla asks, “What happened?,” and I, silent Easter Bunny once more, just shrug. When Ms. Walker and Eric finally rejoin the school, he turns to me, blue egg in hand, adjusts his glasses, and waves.

I grab my own egg—this one yellow—and wave back. And, as a gentle chill glides across the pavement, we each cradle an egg in our hands. We protect them from the cold.