Outside a teepee in rural Kent, a woman waved a smoking bundle of herbs around me, as if I was getting extra attention while going through airport security. I dipped my hand in a bowl of water and dabbed some on my forehead. As instructed, I stepped into the tent, sprinkled tobacco in the fire, and said a prayer.

I was surely the only Presbyterian at this neo-pagan ceremony, a four-day event of fire tending and singing and storytelling to commemorate friends and relatives who had recently died. This made me stand out not just in the teepee, but also in my own country. In 2018, Pew Research Center found that there were more Americans who identified as pagan witches than there were members of the Presbyterian Church (USA). In the seven years since, the liberal-leaning denomination has only continued its long decline, alongside so many other churches across the Western world.

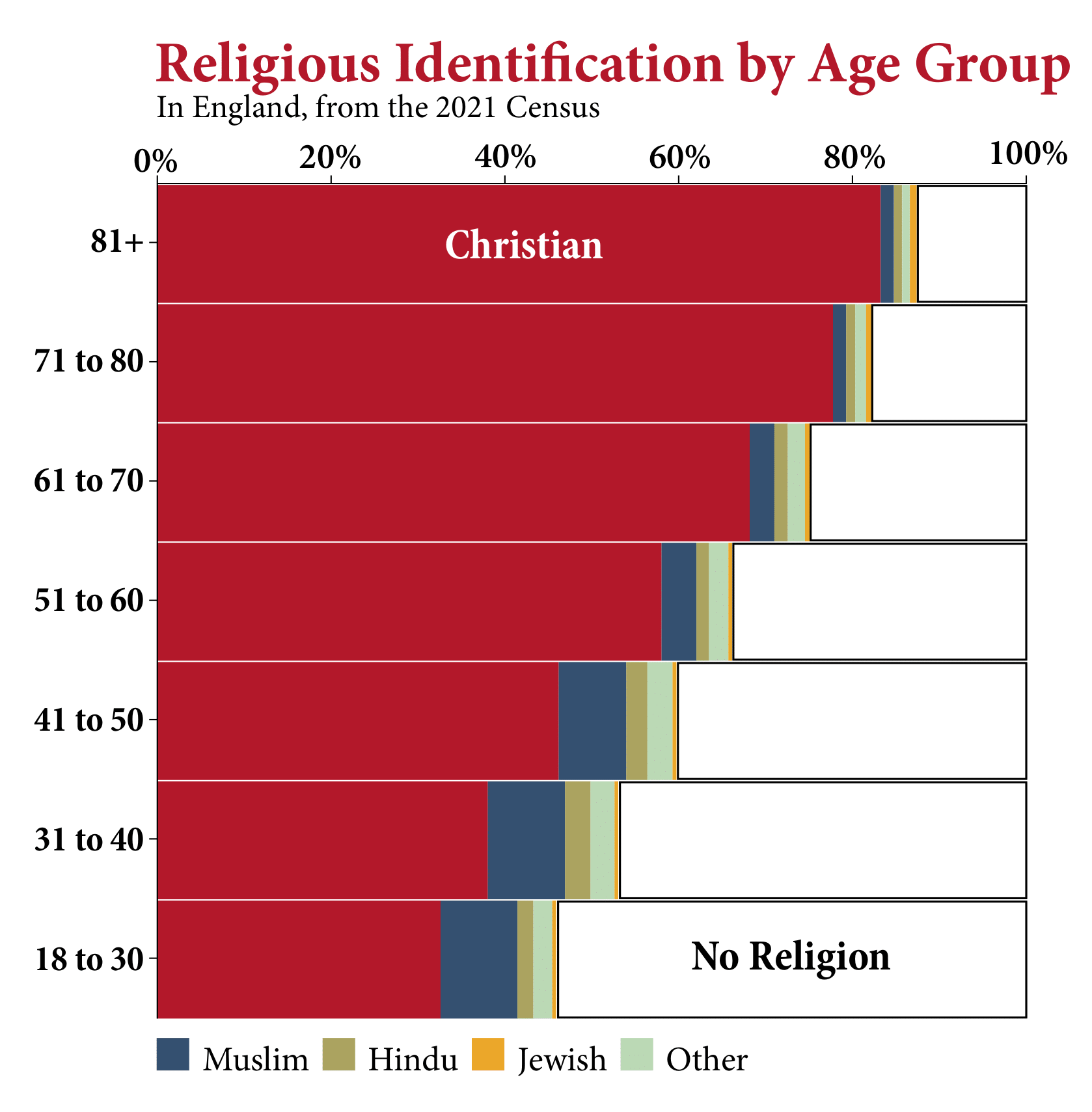

The statistics hardly need repeating at this point. Across the West, people’s participation in religion, its importance to them, and their belief in it have all declined. Oxford’s college choirs keep singing and chapel bells keep ringing, but only a third of English people in their 20s identified as Christian in the last census. But even as the West becomes less devout, many still experience the world as a deeply spiritual and enchanted place.

Image credit: Oscar Reynolds for Cherwell

The days of miracle and wonder

For many intellectuals, religion has been falling out of fashion for centuries. The great German philosopher Friedrich Schleiermacher ran in a circle of friends in the 1790s so secular that he prefaced his book by acknowledging that it would shock them that he defended religion, something they “so completely neglected”. Thomas Jefferson happily predicted that by the middle of the 19th century, every American would renounce the superstitious elements of Christianity and become a more rational Unitarian. The future Christian apologist C.S. Lewis wrote that during his first years at University College, he was “busily engaged (apart from ‘doing Mods.’ and ‘beginning Greats’) in assuming what we may call an intellectual ‘New Look’. There was to be no more … flirtations with any idea of the supernatural, no romantic delusion.”

Despite religion’s continual death in the academy, Christianity and Islam have hardly ever been so alive as they are now in much of the Global South. Devotion is strong in Africa and Asia, continents with the large majority of the global population. But even in the supposedly secularised West, spirituality has signs of life, even if it’s not what it looked like in centuries past.

Yes, an all-time high of 30% of Americans are ‘nones’ – that is, they claim no religious affiliation. But when you probe them, many are deeply spiritual. In a recent survey, less than a third deny the existence of spirits, most believe in God, and most are open to the ideas of heaven and hell.

There is more reason for Enlightenment rationalists like Jefferson to despair. Half of Americans say they definitely believe in religious miracles, and another quarter say they probably believe. And substantial majorities now say they definitely or maybe believe in a whole range of supernatural phenomena you wouldn’t hear about at Sunday school, like Karma, psychic abilities, and (non-Holy) ghosts.

Edward A. David is an associate member of Oxford’s Faculty of Theology and Religion and a lecturer at King’s College London. In a recent pilot study, he analysed how young people from countries across the world understand religion and who they see as spiritual role models.

David told Cherwell: “I’m coming to view religion – at least perceived by Gen Zers – as being a deeply emotive, affect-based phenomenon, not so much doctrine-based or rationally-based, but very much ‘How does this make me feel?’ and going from there.”

Dr. David’s participants from the Global South – both Christian and Muslim – tended to have relatively conservative and traditional religious views. But even in England, traditional religious practices show some signs of revival among Gen Z since the pandemic.

Recent data find a large uptick in churchgoing among young people in England over the last six years, especially among young men. As in the U.S., young men now outnumber young women in churches – an unusual pattern, as women in Christian societies have historically tended to be more devout than men. In the same report, commissioned by the Bible Society and conducted by YouGov, the 18 to 24 cohort was the most likely to definitely believe in God, the most likely to pray regularly, and the most likely to participate in other spiritual practices like meditation.

Many among Gen Z see religion as something of a set of self-help practices. Even those who claim a religious affiliation often draw from a variety of spiritual traditions.

“Gen Z is a generation of authenticity and personalisation, which informs their identities, so their notion of categorisation is much more fluid,” David told Cherwell. “They might land on a certain religious affiliation, but I think if you were to actually ask them, there’d be a much wider spread in terms of religion or spirituality from different traditions informing how they view the world.”

Life and death and life

There were only about a dozen people at that pagan ceremony in Kent – but that was nearly as large as the weekly attendance at the 13th century Anglican parish in the nearest village.

Five weeks later, I was in a much more vigorous ceremony on the other side of the continent. Greeks were flocking to central Athens for Holy Week, kissing icons and crosses, lighting candles, and crowding the streets for a midnight procession singing “Christos Anesti” (Christ is risen).

Did the people squeezed into churches for the Easter vigil skew old, or is it just that Greek people are on average more elderly? Was this an impressive display of the faith of Europe’s most religious country, or a pittance compared to the devotion of previous decades and centuries? I couldn’t tell. The most important bits were all there – the emotion on the faces of old women as the incense came by, the spirit with which the priests read the Byzantine-era liturgy, and my own persistent doubts about whether a word of it could be true – but they couldn’t be readily quantified.

While in Greece, I met a nice young Anglican who is set to be ordained this summer. He told me that he is one of 19 seminarians in his program at Cambridge, where there used to be over triple that number. We talked about the state of our college chapels, and the political weaponisation of Christianity in America, and the Church of England’s declining number of clergy. More importantly, along with thousands of people, we sang Christos Anesti.